Combining Base Editing & Lipid Nanoparticles to Treat Neurodegenerative Diseases

Using Clearpoint Neuro, Base editors, and Lipid Nanoparticles to design a platform for curing rare neurological diseases.

Base Editing to Treat Neurodegenerative Diseases

Thesis:

Combining (1) LNP technologies and (2) Live-MRI Convection Enhanced Delivery will address two challenges currently hindering the administration of base editors into the brain. We will pursue a therapeutic strategy focused on treating monogenic neurological diseases through combining base editor editing efficacy with (a) highly specific neuronal uptake (>90% specificity, enabled by our proposed LNP’s) and (b) best in class therapeutic titration with complete accuracy in the brain (Live-MRI).

Proposal:

The following paper breaks down our proposed strategy into discrete technology vectors - we provide summaries of the relevant research and propose an integrated solution to utilize neuro-focused base editing strategies across multiple genetically-driven neurological diseases. Our strategy seeks to solve two key problems with base editing applications in neuro:

Problem #1: How do we administer cell-type-specific drugs aimed at minimizing off-target uptake in brain cells?

Solution #1: We propose specific lipid nanoparticle formulations surrounding the base editor mRNA complex that will overcome obstacles related to uptake specificity and biodistribution. These obstacles include liver degradation of LNPs, micelle formation risks, and the inherent issues around drug substances efficiently crossing the blood-brain barrier (BBB) from systemic circulation (e.g., intravenous/Zolgensma or oral/Risdiplam). Recent advancements in LNP technologies facilitate targeted uptake into predetermined brain cells of interest, further supporting the objective of precise and controlled delivery of base editors within the brain.

Problem #2: How do we enable surgeons to accurately target specific brain regions of interest (such as the lateral ventricles, putamen, or subthalamic nucleus) while minimizing unintended distribution?

Solution #2: Live-MRI-guided delivery of specific LNP particles will allow surgeons to quantitatively and visually assess the deposition of biologics within the intended brain region in real-time and with high degrees of accuracy, thereby enhancing the likelihood of effective targeting, precise injections, and optimal drug exposure.

We provide solutions to these problems across four separate sections:

(1) Section #1 - Coating LNPs for Neuronal Specificity: We propose an LNP structure that will achieve specificity in targeting neurons, including (1) the structure of the amine head, and (2) a tail composed of an acrylate group, a biodegradable disulfide bond, and cholesteryl moieties. We believe base editor mRNA will fit within this design construct, thereby enhancing the selectivity of the editing process within neuronal cells. For now - we focus on neuron-specific diseases, but we recognize the potential to expand into adjacent cell-types across neurological genetic diseases over time.

(2) Section #2 - Live-MRI Delivery: How ClearPoint’s Live-MRI medical device technology suite is designed to increase drug biodistribution, while minimizing off-target exposure.

(3) Section #3 - Base Editing: Based on the work by Arbab et al. (2023), we describe in vivo proof of concept success within a neurological indication by base editing.

(4) Section #4 - Proposed Base Editing Constructs: We propose base editing constructs that will apply to various other monogenic neurological diseases.

Table of Contents

Section #1 - LNP Formulation with High Specificity for Neurons

Part #1: Proposed Ionizable Cation Structure and 80-OCholB LNP Construct

Part #2: Comparing cell membrane uptake and endosome formation characteristics of our proposed LNP amine head construct vs. current commercial therapies

Part #3: Endosome release

Part #4: Biodegradation

Part #5: Specificity and biodistribution for our proposed LNP construct vs. AAV’s

Part #6: Reducing immunogenicity of amine groups in neuro conditions leads to improved extracellular bioavailability

Part #7: Specificity from base editors

Part 8: Conclusion

Section #2: ClearPoint Neuro’s SmartFlow Cannula + SmartFrame Array technologies create efficient delivery rails into the brain

Part #1: Issues with standard neurological delivery mechanisms and our proposed solution

Part #2: Technical Advantage - convection-enhanced delivery

Part #3: Stepped cannulas limit reflux, a critical consideration for CED

Part #4: Real-time imaging reduces complications by permitting detection of reflux, leakage, and adjustment of treatment delivery to reduce adverse effects

Part #5: AAV gene therapy delivery and distribution data using Clearpoint Neuro’s system

Section #3: Evidence of Base Editing in Neurodegenerative Disease

Section #4: Future Indications Where we Will Apply the Platform Technology

Part #1: Pipeline of target diseases

Part #2: Disease physiology and regions of interest we will seek to target

Part #3: Proposed Guide RNA construct design

Part #4: Projected market opportunity and valuation

Risks to our Thesis

Citations

Section #1 - LNP Formulation with High Specificity for Neurons

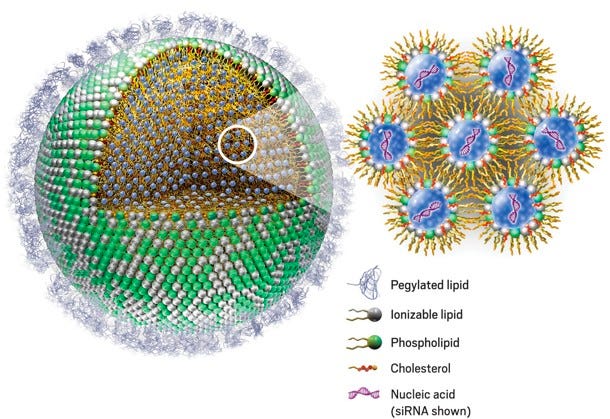

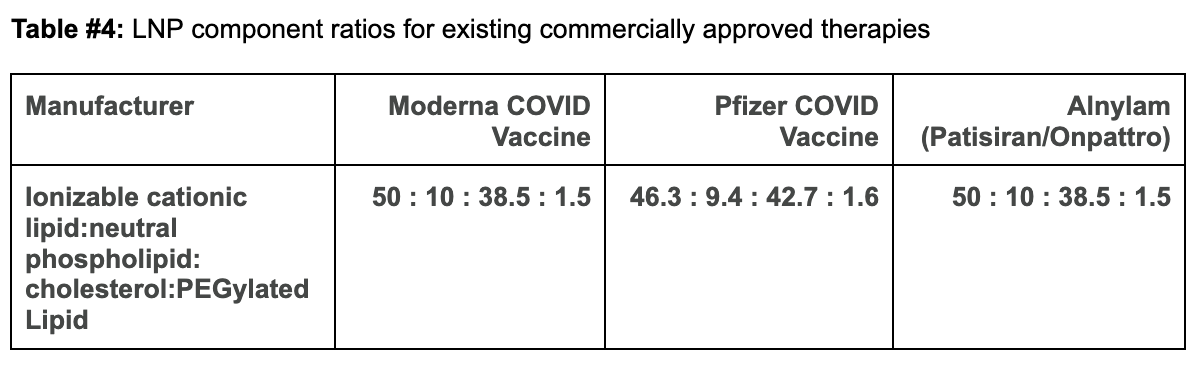

The key design components of an LNP include the (1) Ionizable cationic lipid head and (2) the PEGylated lipid. Section #1 proposes an LNP construct, including the atomic designs for both of the lipid components mentioned.

We seek to (1) Explain the neuron-specific delivery characteristics created by our proposed cation LNP design, (2) Outline how our proposed PEGylated construct reduces the expected immunogenic profile in the brain, and (3) Confirm how the addition of base editor mRNA will enable maximum on-target editing efficacy, while retaining specificity to neurons when encapsulated by our LNP construct.

Section #1 | Part #1: Proposed Ionizable Cation Structure and 80-OCholB LNP Construct

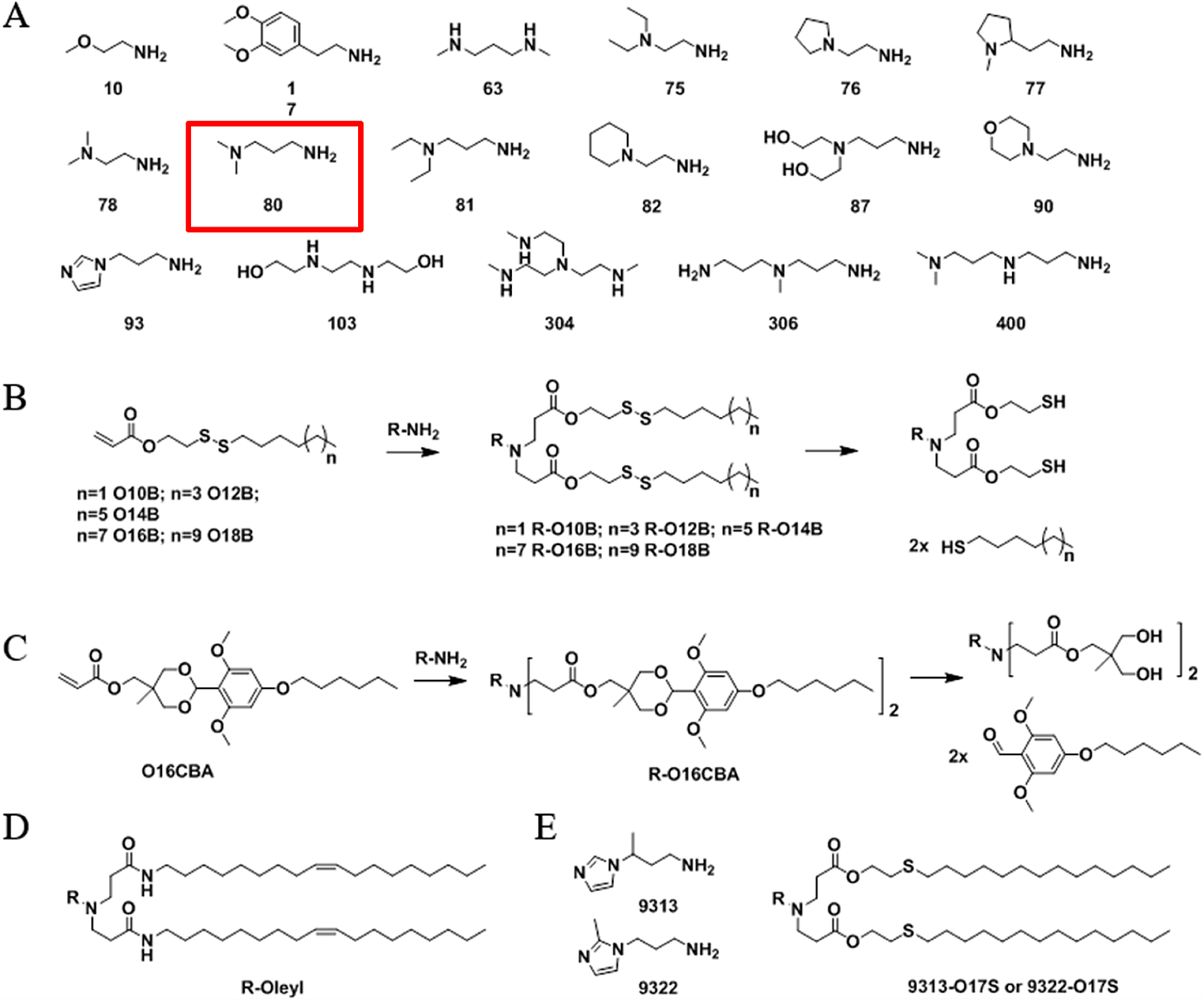

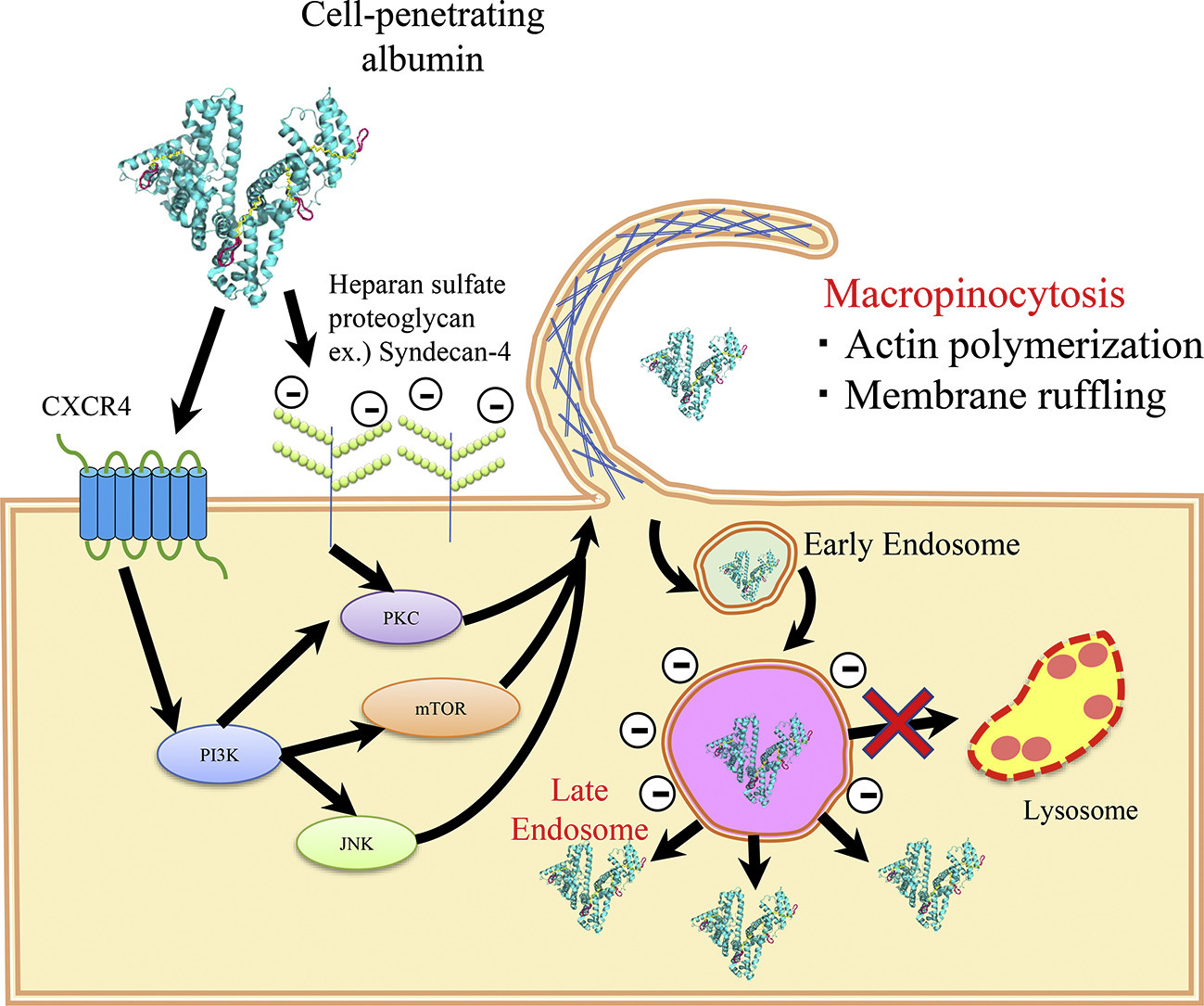

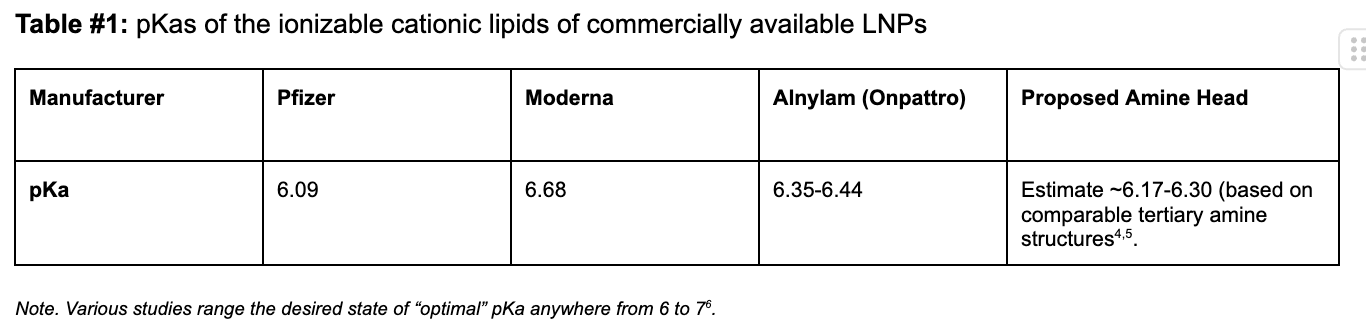

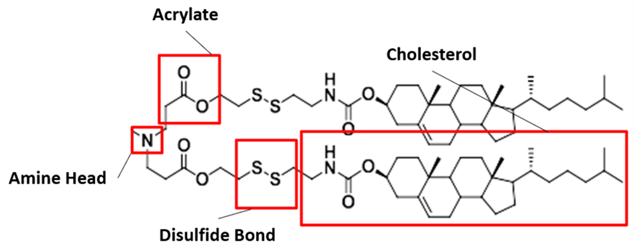

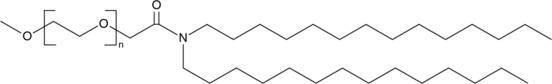

Our proposed ionizable cationic lipid construct utilizing the #80 amine group is flagged below1. We will pair the amine group with two disulfide bond-containing biodegradable tails that are attached to a cholesteryl group.

In vivo evidence suggests this combination will exhibit greater selectivity for neurons vs. nearby cells in the brain (i.e. astrocytes, microglia, and oligodendrocytes). Note - our proposed lipid design also exhibits cell type specificity greater than that normally seen in standard AAV constructs (data below).

Figure #1: Chemical structures of (a) Amine heads and (b) OCholB tails. We propose utilizing an amine head #80, paired with an OCholB tail (80-OCholB)

Amine Head Construct:

OCholB Tail:

Combined amine head #80 and OCholB tails (Note - NH2 in the #80 amine head above corresponds to the boxed “Amine Head” with three carbon bonds shown in the image below):

Figure #2: Proposed LNP ionizable cation construct (First developed by Li et.al., 2020)1

Section #1 | Part #2: Comparing cell membrane uptake and endosome formation characteristics of our proposed LNP amine head construct vs. current commercial therapies

We believe our proposed ionizable cation structures will provide the basis for favorable cellular uptake of the LNP construct. Below, we briefly highlight the mechanisms behind LNP endocytosis, in addition to the key risks around micelle formation that may impede successful LNP uptake.

Biology of LNP uptake by cell membranes:

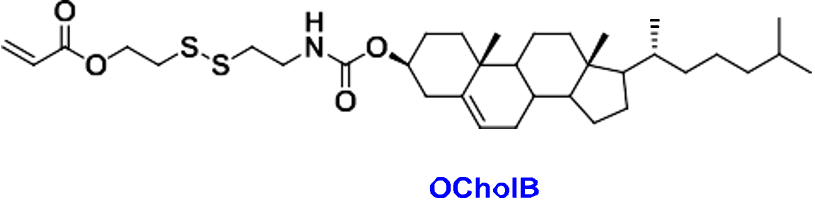

In vivo, the neutrally charged amine head (inducible cation) is brought into cells through receptor-mediated endocytosis (using clathrin) or receptor-independent endocytosis (macropinocytosis)2. Examples of receptor-mediated processes include the uptake of LNP-siRNAs delivered to the liver through Apolipoprotein E (ApoE) and low-density lipoprotein receptor (LDLR)3. Clathrin-mediated endocytosis occurs via the binding of a ligand to a specific cell receptor, resulting in the recruitment of adaptor proteins (e.g., AP-2) and clathrin3. Clathrin, a protein that forms a triskelion shape, polymerizes to form a lattice-like coat that shapes the membrane into a vesicle. As the clathrin lattice grows, the pit forms a vesicle and the dissociation of the complex is facilitated by dynamin. Then, ATPase Hsc70 and auxilin remove the clathrin coat and free the vesicle to fuse with early endosomes to form late endosomes.

Figure #3: Mechanism of clathrin-mediated endocytosis

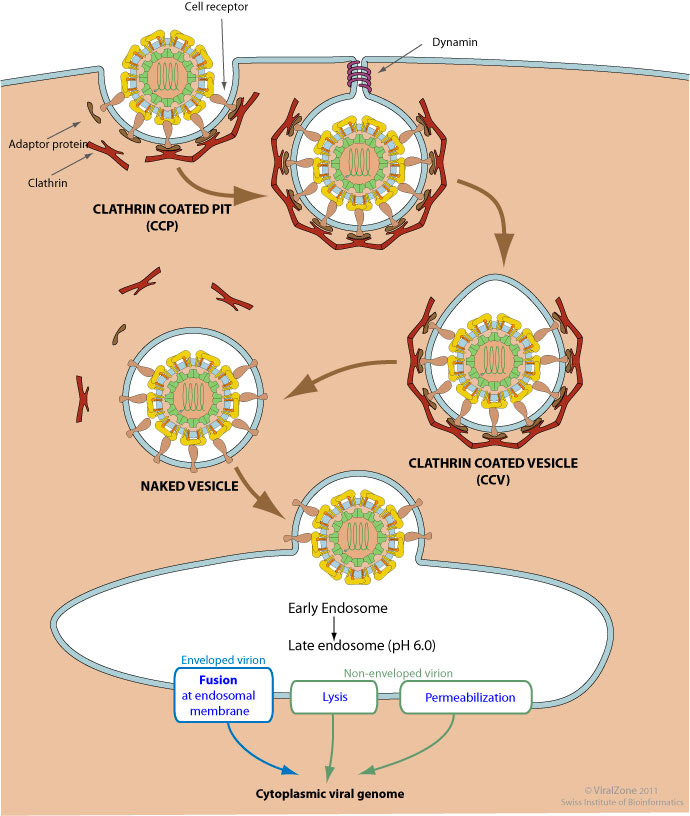

On the other hand, macropinocytosis is initiated by the activation of growth factor receptors leading to actin polymerization and membrane ruffling. This dramatic rearrangement leads to the wave-like protrusions of the membrane (i.e., ruffles) that can fold back on the membrane and create a large macropinosome. The vesicle starts out as an early endosome and then matures into a late endosome and eventually is degraded by lysosomes.

Figure # 4: Mechanism of macropinocytosis

Potential for toxicity through micelle formation:

LNP toxicity towards native cells is primarily dependent on micelle formation. Micelles are small spherical lipid constructs consisting of a hydrophilic exterior and hydrophobic interior, which are created as a byproduct of cell membrane disruption by an LNP. The LNP construct’s pKA profile is the key metric that determines this likelihood of micelle creation.

The probability of micelle formation is higher for positively charged amine head groups (blue positive lipid in Figure #5 below) versus neutral amine head groups. Note - the external-facing amine heads comprising a portion of the lipid bilayer in our proposed construct, as well as the Moderna/Pfizer COVID-19 vaccines, are neutral upon cell uptake.

In the scenario of a positively charged head group (red lipid below), the lipid is drawn to the negatively charged phospholipids comprising the cell membrane. Normally - seamless uptake of the LNP by the cell membrane occurs. At a certain concentration and charge level for the positive amine head, however, this uptake leads to membrane disruption and micelle formation. The critical micelle concentration (CMC) is the concentration of positive cation molecules residing in the LNP membrane that would result in micelle formation. A higher CMC naturally results in decreased micelle formation—thereby reducing cell lysis or membrane disruption.

Figure #5: Formation of micelles due to cationic lipid (LNP) toxicity

Energy favorability and steric stabilization play key roles in regulating micelle creation. At the same cation concentration, a stronger charge would lead to greater electrostatic repulsion between the outer cation portions of the micelle, thus decreasing micelle stabilization and resulting in fewer micelles formed. Additionally, a stronger cation charge surrounding the LNP results in favorable interactions between the LNP cation and the negatively charged elements of the cell membrane layer, which may make it less energetically favorable for the cation to pull away and form individual micelles.

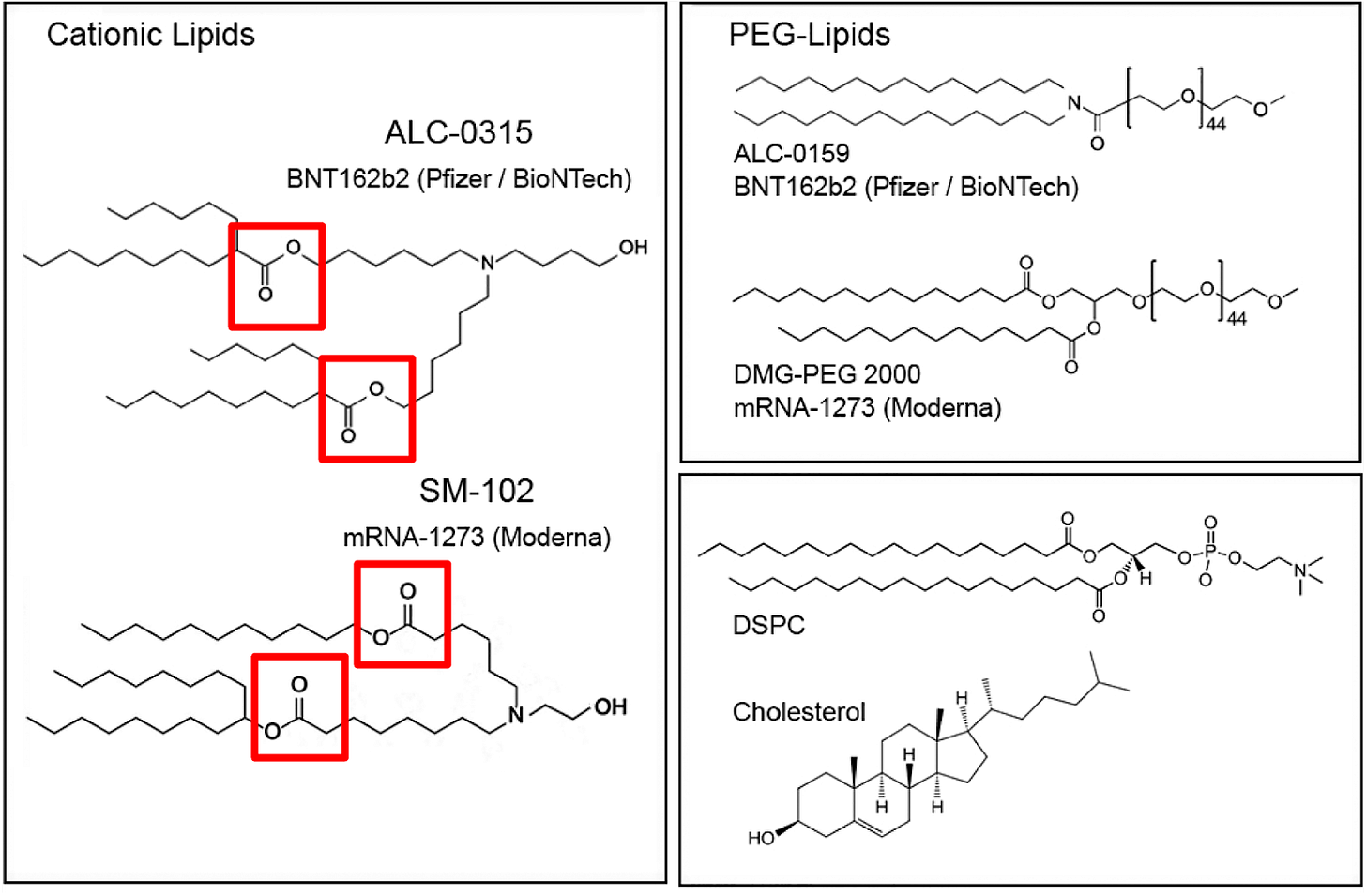

Comparing Moderna and Pfizer’s LNP constructs to our proposed design:

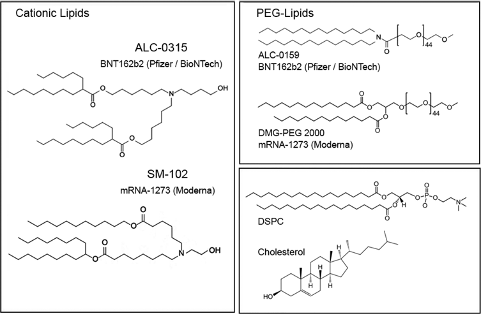

The ionizable cationic lipid constructs used by the successful Pfizer (ALC-0315/Top) and Moderna (SM-102/Bottom) COVID-19 Vaccines are shown in Figure #6 below.

Figure #6: Pfizer & Moderna ionizable cationic lipid constructs

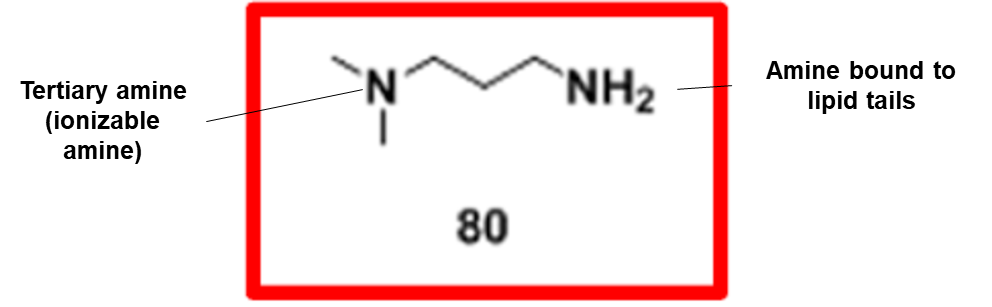

Our proposed cationic LNP construct (Figure #2) contains a tertiary amine that can become protonated, similar to those present in the Pfizer and Moderna ionizable amino heads. Empirically, as shown below, the pKa’s of lipid constructs comprised of tertiary amine structure groups similar to ours are within the range of the pKa’s exhibited by Moderna and Pfizer’s amine heads—giving us conviction that the compelling specificity evidence (data below) seen by Li et al. (2020) is sound.1

Table #1: pKas of the ionizable cationic lipids of commercially available LNPs

Section #1 | Part #3: Endosome release

Characteristics of our amine head that will drive protonation and thus early mRNA release

LNPs containing ionizable cation lipids are primarily protonated (positively charged) during manufacturing to maximize the electrostatic interactions with nucleic acids and optimize loading efficiency. When they are transferred to the body, the bloodstream’s pH keeps the cationic lipid deprotonated. The neutral charge prevents degradation by Kupffer cells in the liver and splenic macrophages because the scavenger, toll-like, mannose, and Fc receptors involved in this pathway primarily target charged nanoparticles7.

Once the LNPs are brought into endosomes, the local acidic pH leads to the protonation of the cation head, and the positive charge destabilizes the endosomal membrane to promote cytosolic delivery of the genetic cargo. Specifically, the positive charge of the cation head incites the flip-flop reorganization of anionic phospholipids in the endosomal membrane bilayer, where the anionic phospholipids in the endosomal membrane shift towards the inner leaflet of the membrane and are pulled towards the positively charged LNP cations within the endosome. This process neutralizes the charge, leads to degradation in endosomal structure, and causes the dissociation of the negatively-charged LNP cargo (mRNA) into the cytoplasm.

LNPs are concentrated primarily in earlier stage endocytic compartments upon cell membrane uptake. Once early endosomes become late endosomes or are transported to lysosomes, the probability of RNA release is reduced. Only a small fraction (~1-2%) of RNAs are thought to be released from endosomes8.

We believe that our proposed amine head construct (below) directly influences the probability of endosome escape upon cell membrane internalization due to its ionizable nature.

Specifically - the presence of an amine group (nitrogen on the right) that is ~3 molecules away from the ionizable tertiary amine (nitrogen on the left) in our cationic lipid head construct increases the likelihood of the tertiary amine becoming protonated. A partially negative intramolecular dipole is formed within the ester group portion of our lipid tail construct (“Acrylate” labeled group below), pulling electrons away from the amine head group directly bound to those tails.

These interactions lead to a partially positive intramolecular dipole in the amine bound directly to the tail (labeled “amine head” in the structure above), making the other amine head group (tertiary) slightly more negative and thus increasing the propensity for its protonation. In this scenario, an enhanced likelihood of tertiary amine group protonation directly raises the probability that the entire construct will drive endosomal membrane degradation through interactions with the anion phospholipids in the membrane. As a result - mRNA cargo is released into the cytoplasm and transcribed.

Advantages of our proposed ionizable cationic lipid structure vs. Moderna/Pfizer’s constructs

Our proposed LNP construct contains carbonyl groups directly adjacent to the amine closest to the lipid tails. As a result, the dipole interactions driving the partial positivity of this amine head are larger, resulting in a more negative dipole created on the remaining “non-head” amine group in our structure. This “non-head” amine head group is thus more amenable to protonation.

On the other hand, in the Moderna/Pfizer construct, there is only one amine group. This compound is bound to the lipid tails and contests with the molecular electronegativities from two separate carbonyls and a hydroxyl group. As a result, the partially positive dipole created on this amine is higher than that created in our proposed structure, which correspondingly makes the Moderna/Pfizer nitrogen’s propensity to gain a proton (e.g., pKA) and cytosolic delivery (due to endosomal degradation) lower. We estimate that our pKA is at the higher end (~6.5+) than those for Moderna (6.68) and Pfizer (6.09). However, comparable pKA ranges for individual LNP constructs with similar amine heads, disulfide bonds, or cholesterol tail groups border ~6.17-6.30, which indicate that further experimentation is required.

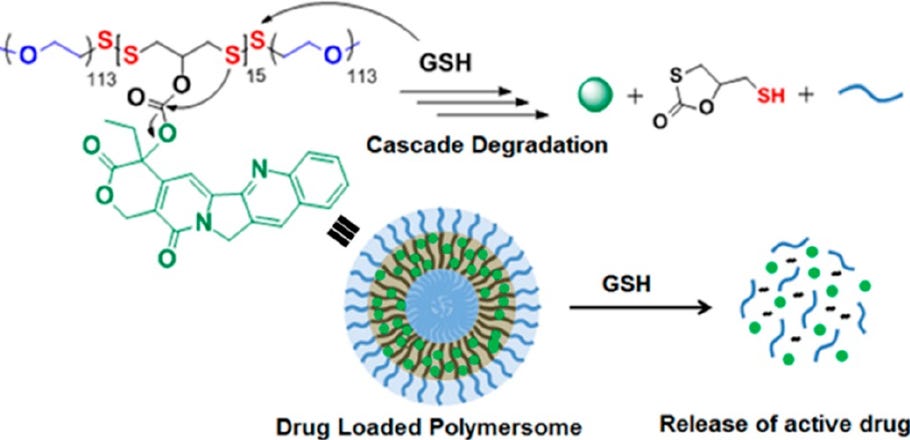

Advantages of disulfide bonds present on the lipid tail

Disulfide bonds in the tail are also thought to be important for endosomal release of the nucleic acid. Disulfide bond-containing materials are primarily cleavable in the presence of reducing factors such as glutathione (GSH). The exact mechanism includes the following steps: 1) Nucleophilic attack of the disulfide bond by the SH group in GSH; 2) Transfer of the disulfide bond from the LNP to GSH, forming glutathione-disulfide; and 3) Reduction of glutathione-disulfide back to GSH by glutathione reductase.

Figure #7: Example nanoparticle undergoing GSH-mediated degradation

Since there are more reducing factors like GSH in the intracellular space versus the bloodstream, disulfide bond-containing nanoparticles like ours are thought to be stable in the blood and cleaveable only after cell internalization (see figure below). Therefore, we hypothesize that disulfide-bond containing LNPs exhibit increased cargo release into the cytoplasm.

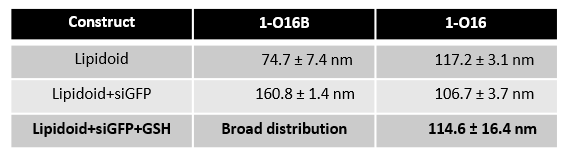

Indeed, in one experiment (table below), R-O16 (an LNP with a linear tail) demonstrated less efficient release of cargo than R-O16B (the same LNP with a disulfide bond in the tail)9. The third row in Table #2 below confirms that, when surrounding an RNA construct (siGFP) in the presence of GSH, the O16B construct containing the disulfide bond is fully degraded. This is indicated by the “Broad distribution” value in Table #2, corresponding to a fully degraded LNP with no lipid integrity to be measured, vs. the O16 retaining structural integrity.

In sum - we believe the addition of a disulfide bond to our proposed LNP construct provides catalysis benefits that will lead to more efficient mRNA cargo release into the cellular cytoplasm.

Table #2: Hydrodynamic mean diameters of lipidoid-siGFP nanoparticles in the absence and presence of GSH

Section #1 | Part #4: Biodegradation

Ester linkages (Acrylate Group) enabled better degradation

The presence of ionizable tertiary amine based ester lipids, on the whole, are shown to induce rapid clearance from blood due to ester linkage cleavage. Linkers are classified as non-biodegradable (e.g. ethers and carbamates) and biodegradable (e.g. esters, amides, and thiols). Biodegradable linkers demonstrate rapid clearance in vivo, thereby reducing the innate immune reaction. Notably, the LNPs contained within the COVID-19 vaccines, SM-102 (Moderna) and ALC-0315 (Pfizer), contain ester linkers (red boxes in figure below).

It’s reasonable to believe our proposed LNP construct is more susceptible to hydrolysis. The presence of the covalent ester bond further away from the positively charged amine groups in the Pfizer/Moderna constructs, vs. our proposed LNP construct, increases their overall resistance towards liver degradation. Pushing the ester group farther away results in decreased partial positive dipoles on the amine group and therefore reduces the probability of nucleophilic attack by H2O. This makes the ester less susceptible to hydrolysis and thus degradation and clearance.

Given our proposed LNP contains an amine group in closer proximity to the ester groups in the lipid tails, we would imagine that this amine would drive increased positive polarity and thus H2O attraction, making our ester more susceptible to in vivo hydrolysis. Our proposed mechanism of delivery - Live-MRI Convection Enhanced Delivery - in theory reduces this risk given we plan to directly administer the compound into the brain, vs. risking liver degradation.

Note - between the Pfizer and Moderna constructs, the Pfizer product demonstrates an increased ability to resist degradation in the liver as shown by the EMA documents assessing Pfizer’s vaccine. This might be explained by Moderna’s SM-102 containing both branched plus linear lipid tails vs. Pfizer’s construct with two linear tails. The presence of a single tail with Moderna likely contributes to a higher accessibility for cleavage of the ester bond. With regards to our proposed molecule, the cholesterol component of the lipid tail likely results in added steric hindrance. But - we see the addition of a disulfide bond as overcoming this barrier because our molecule is more susceptible to a separate degradation pathway via GSH.

Section #1 | Part #5: Specificity and biodistribution for our proposed LNP construct vs. AAV’s

Various serotypes of AAVs have demonstrated preferential tropism towards specific tissues and cell types, attributable to the differential expression of receptors on the cell surface. However, even within a specific tissue, heterogeneity in AAV transduction can manifest due to the complex interplay of viral capsid, cell surface receptors, and intracellular trafficking pathways.

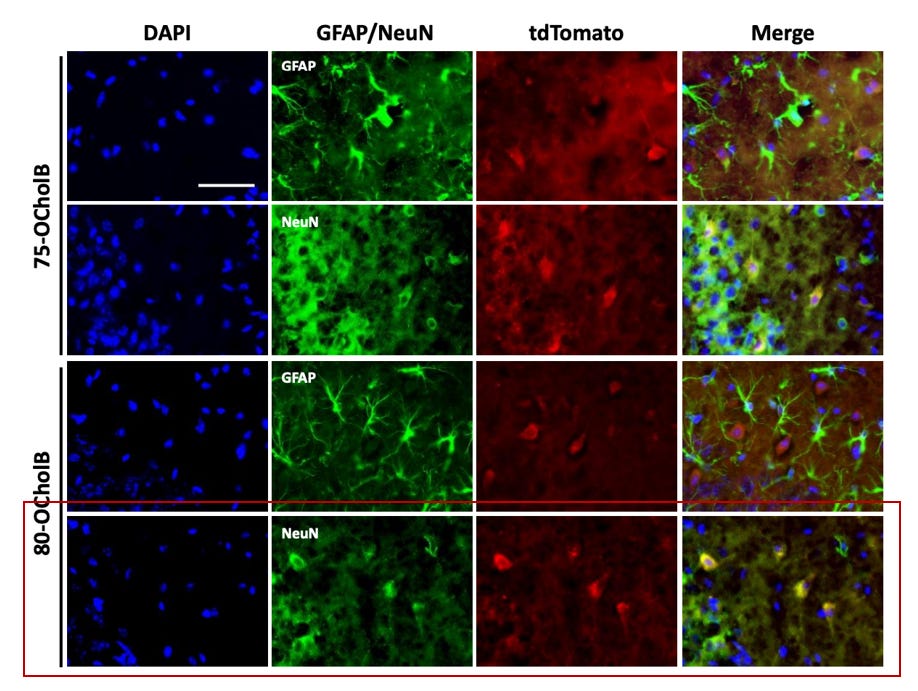

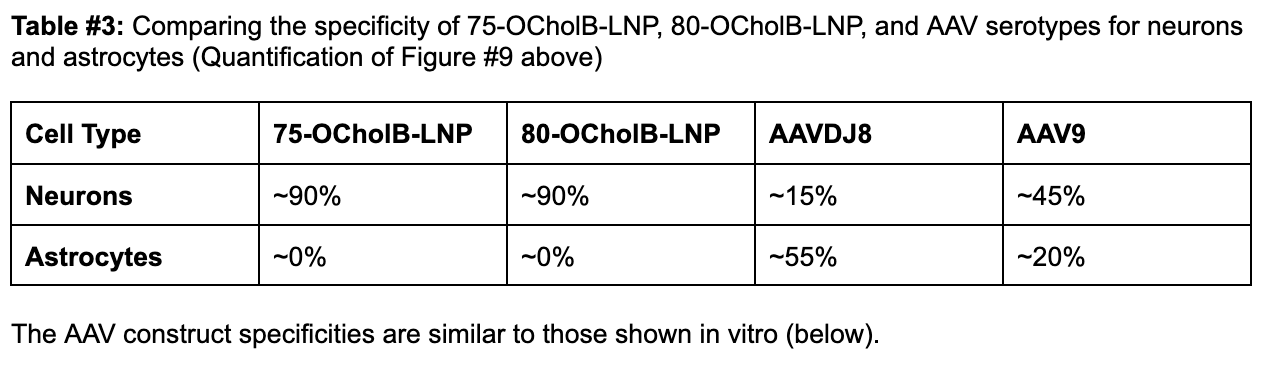

For base editing, precision is an absolute requirement. A lack of specificity in delivery could lead to suboptimal therapeutic responses and, at worst, off-target effects that could precipitate unanticipated genetic alterations in non-target cells. Our proposed LNP construct (80-OcholB) is remarkably neuron-specific (Figure #8 below), in comparison to AAV9, which is the preferred AAV serotype for CNS administration (See Table #3 below).10

Proposed LNP specificity to neurons:

In the figure below - DAPI is used to stain for all cells (blue). Green stains for astrocytes (GFAP) and neurons (NeuN) respectively. TdTomato+ cells indicate areas of uptake of the mRNA-LNP complex. Yellow staining in the merged panel indicates co-localization and uptake into the respective cells.

Our proposed construct is 80-OCholB (red box). Merged staining in row three indicates that astrocytes display very limited co-localization with 80-OCholB. However, row four merged staining confirms the remarkable specificity profile to neurons.

Figure #8: The in vivo specificity of 75-OCholB and 80-OCholB as measured by fluorescence staining

Additional in vivo experimentation (shown below) demonstrates that 75-OCholB and 80-OCholB colocalize to neurons with ~90% efficiency versus to astrocytes with ~0% efficiency.

In comparison, in vivo administration of AAV9 demonstrated up to ~45% uptake by neurons and ~20% by astrocytes, which is a much worse specificity profile. ~45% uptake is denoted by the blue “TH” bar in Figure #9 below (neurons) vs. ~20% in S100B (astrocytes). In vitro experimentation demonstrated varying neuron-astrocyte specificity profiles depending on AAV serotype but none of these options were as neuron-specific as our proposed LNP (Right side of Figure #9).

Figure #9: Comparing the in vivo specificity of 75-OCholB/80-OCholB with AAV serotypes

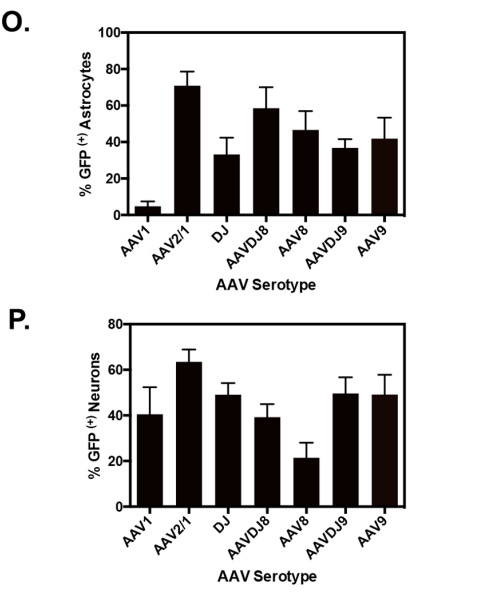

In vivo delivery specificity of AAV vectors (left) or LNPs (right) to astrocytes and neurons. For the AAV experiment, the y-axis describes % GFP (a proxy for AAV uptake) for each serotype. Neonatal mice were injected through intracerebroventricular (ICV) administration. Viral solutions were diluted in PBS at 1 * 1010 genome copies (GC)/µL and injected at 2 µL/hemisphere, equivalent to an absolute quantity of 2 * 1010 GC/hemisphere. Uptake into astrocytes (S100B) and neurons (TH) is denoted by their respective markers. Pretreatment included taking neonatal pups and inducing them with hypothermic anesthesia by inserting the mice onto a cold aluminum plate placed on ice. The anesthesia administration was confirmed by a neonatal color change of the mice from pink to purple, squeezing of the paw, and cessation of movement before injections. Ventricular injection sites were identified by ⅖ distance from the lambda suture (junction point of sagittal and lambdoid sutures, where skull bones meet near the back of the head) to the eye and 3 mm ventral from the skin.6 For the LNP experiment, the co-localization of the LNPs was tested utilizing cell-specific markers (GFAP for astrocytes and NeuN for neurons). Mice were continuously infused with mRNA/LNPs (lipidoid = 0.25 mg/mL, mRNA = 0.025 mg/mL) through a brain cannula into the lateral ventricle from day 1 to day 4. Mice were sacrificed on day 9, and brains and spinal cord were sectioned into slices for analysis. Pretreatment included loading the mice with an ALZET osmotic pump (Model 1003D) for infusion11. The brain infusion kit cannula is 9.3 mm in height, 10.0 mm in length, and 3.4 mm in diameter. Steps for loading cannula included determining stereotaxic coordinates, calculation of the desired cannula length (usually ~2-3 mm), administering depth adjustment spacers to alter cannula depth and verification of the length of the tube. The pumps were removed on day 4.12

The AAV construct specificities are similar to those shown in vitro (below).

Figure #10: In vitro specificity of AAV serotypes to neural cells

In vitro delivery efficacy of different AAV serotypes to astrocyte (top) and neuron cultures (bottom).13 For the experiments, primary cortical neurons were isolated from neonatal mice and then seeded on Poly-D-Lysine coated 12-mm coverslips at a 5.0 * 104/well density. Neuronal cultures were grown for 7 days prior to viral treatments. Mixed glia were seeded 24 hours prior to transduction. All AAV-GFP serotypes were diluted to 5 * 1010 GC/ml in neurobasal medium for neurons. For mixed glia, a higher titer was needed of 1.9 *1011 GC/ml. The native GFP fluorescence signal was monitored at 488 nm/519nm on a plate reader. Cells were immunostained for GFP (both), MAP2 (neurons), and GFAP (astrocytes).

Section #1 | Part #6: Reducing immunogenicity of amine groups in neuro conditions leads to improved extracellular bioavailability

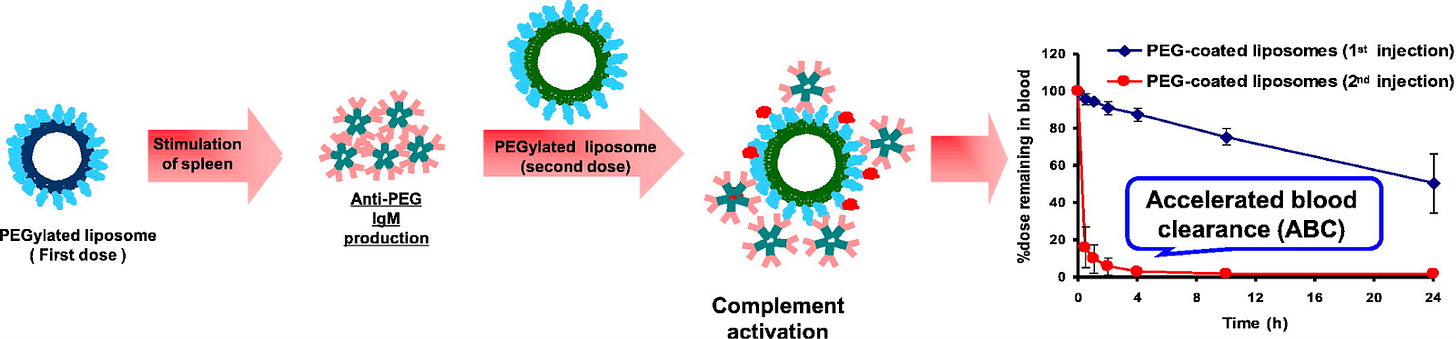

Adverse immune reactions through opsonization, which is the process of marking foreign particles for destruction by the immune system, poses the greatest risk to the immunogenicity profile of LNP therapies. PEGylation, the attachment of polyethylene glycol (PEG) chains to lipids, is essential for enhancing LNP stability, reducing degradation, and improving biocompatibility. The presence of hydrated PEG brushes is believed to shield antigenic epitopes from immune recognition, as the PEGylated lipid constructs influence the immune response through attracting H2O, thereby creating a hydrophilic cloud around the LNP/Protein Corona. Also - PEGylated lipids aid in inhibiting LNP aggregation and reducing the propensity for uptake by immune cells.

PEGylated Lipid-Directed Immune Response:

Two key immune risks to PEGylated lipid inclusion are (1) The generation of anti-PEG antibodies (Abs) and (2) Opsonin recognition of circulating LNP’s.

This anti-PEG Ab phenomenon is characterized by an IgM antibody response to the initial administration of PEGylated lipids. The immune response to PEGylated LNPs is mediated by B cells. B cell receptors (BCRs) bind to PEGylated lipids, leading to BCR cross-linking and activation of B-cell linker (BLNK), initiating a signaling cascade that causes B cell differentiation into plasma cells. Plasma cells secrete anti-PEG antibodies, which can trigger the complement pathway and result in the removal of PEGylated LNPs from circulation.

The IgM antibodies initiate the complement pathway through opsonization, where they bind to PEGylated lipids and expose the Fc region of the antibody. This binding leads to phagocytosis, resulting in the clearance of the lipid from circulation14.

Figure #11: PEGylated lipid interactions with complement proteins & Ab’s.

Circulating LNP’s are also recognized by opsonins, which include immunoglobulins, fibronectin, apolipoproteins, and complement proteins. Opsonization renders LNPs more susceptible to phagocytosis by cells in the mononuclear phagocyte system (MPS). Opsonization occurs due to a combination of hydrophobic, electrostatic, and hydrogen bonding interactions.

MPS cells uptake LNPs through complement, Fc, and fibronectin receptors. Taken together, the uptake, distribution, and stability of LNPs is influenced by several tens to hundreds of types of serum proteins that readily interact with circulating nanoparticles (NP), thereby forming a protein corona on the NP surface. Therefore, protein absorption plays a role in both the reduction of circulation time (Ab/Opsonin-mediated uptake) and the specificity of LNPs for cell types15.

Figure #12: LNP structure

PEGylation plays a crucial role in enhancing the stability of lipid nanoparticles (LNPs) by sterically precluding LNPs from interacting with neighboring molecules and utilizing the construct’s flexibility to add a large conformational freedom to the surface of an LNP, thereby resulting in foreign molecule integration becoming thermodynamically unfavorable16. The interaction between PEG chains and water molecules creates a hydration layer around the particle, increasing its size and hindering the penetration of other particles. PEG chains' flexibility prevents foreign molecules from reaching the nanoparticle's surface17. Studies have shown that PEGylation increases the blood circulation half-life of liposomes >10-fold18, with longer PEG-lipid anchors providing more stable carriers.

Our proposed amine head construct which successfully displayed selectivity to neurons in mice did not contain a PEGylated lipid component in its initial research. We are proposing Live-MRI enhanced delivery to maximize the probabilities of infusion into desired brain regions of interest (described further in Section #2), and will further investigate the necessity of various PEGylated conformations to reduce the innate immunogenic responses anticipated within brain tissue.

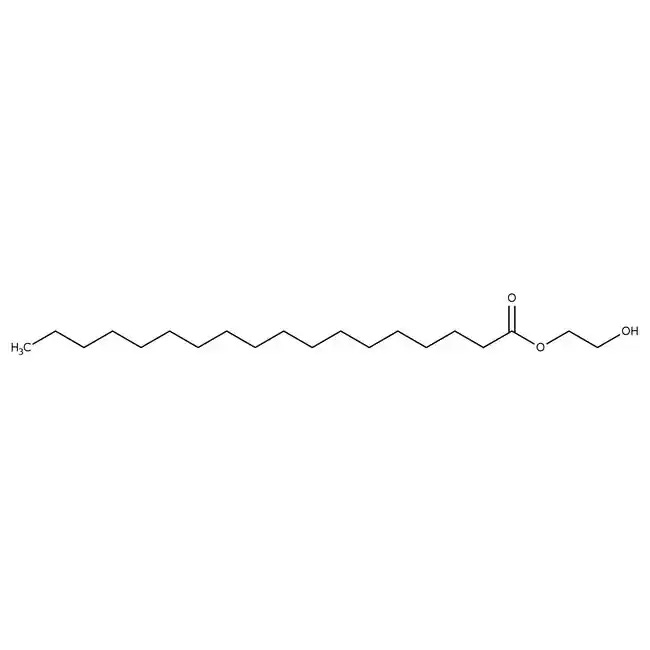

Real-world comparisons between PEGylated solutions and our proposed amine head construct

Moderna and Pfizer both utilized pegylation in their COVID-19 vaccines—DMG-PEG(2000) and ALC-0159 respectively.

Figure #13: Pfizer PEGylated lipid - structure of ALC-0159

MW: 2450.0 g/mol

Structure: C121H243NO47

Figure #14: Moderna PEGylated lipid - structure of DMG-PEG (2000)

MW: 2509.20 g/mol

Structure: C122H242O50

Figure #15: Our proposed PEGylated lipid

MW: ~1600.8 g/mol

Structure: C100H200O43

Generally, with pegylation, molecules with increasing PEG molecular weight (and longer chain length) lead to a thicker layer that shields the surface from foreign molecules due to more rigid steric interactions19. The tighter packing enables longer circulation due to reduced absorption of proteins and macrophage recognition. In fact, 2kDA (2000 g/mol) molecular weight is usually required at minimum to shield NP surfaces from macrophage clearance.

However, in addition to molecular weight, the physicochemical properties of the entire nanoparticle can influence protein adsorption and circulation time. Larger NPs (composed of a larger lipid and/or PEGylated chain) may exhibit stronger adherence to macrophages vs. smaller NPs due to increased stochastic/freestanding interactions between the larger, higher entropy, PEG chains and foreign molecules.

In addition, surface density plays a key role. When PEGylated lipids comprise >10% of the total surface lipids, this tends to inhibit LNP aggregation. If the average distance between neighboring PEG chains (D) is greater than the Flory radius (RF, which equals aN3/5 where N is the degree of polymerization and a is monomer length), then the PEG chains will not overlap and instead form a mushroom layer. If Rf > D, the adjacent PEG chains overlap, forming a brush-like configuration. Generally, a higher surface density resists adsorption of external compounds due a more neutral zeta potential, which is difference in electric potential at the junction of the surface and fluid. A neutral zeta potential is helpful because it limits the risk for particles clumping together to form insoluble or toxic compounds.

Figure #16: Surface & zeta potential of LNP’s

We propose utilizing a PEG solution that has been proven to demonstrate a limited inflammatory response in the brain: 3 mg polyethylene glycol monostearate with an ethylene glycol polymerisation degree of 40 (Figure #15)20. Our PEG solution has a molecular weight (~1600.8 g/mol) that is slightly less than the molecular weights of Pfizer (~2450.0 g/mol) and Moderna (2509.20 g/mol).

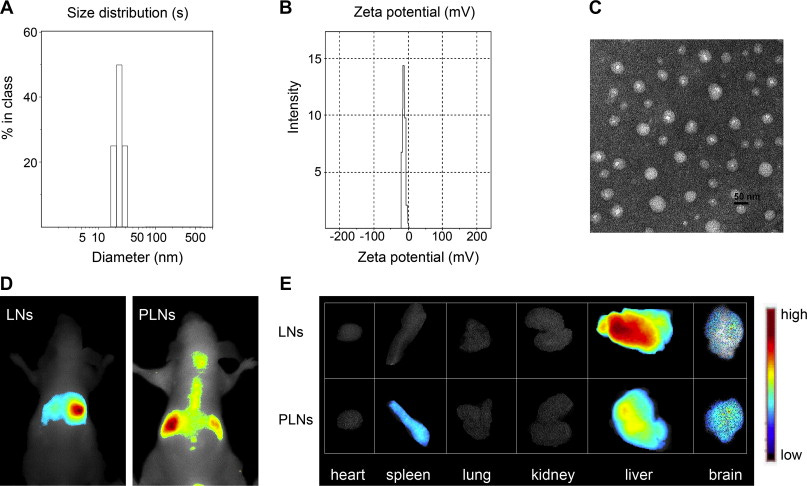

In vivo activity of our PEGylated construct

In vivo data for our proposed PEGylated LNP (Figure #17) supports that our molecule likely does limit the microglia activation in the brain, potentially due its molecular weight being close to the 2kDA guideline and given the brain’s immune reaction is not as strong as that in systemic circulation. Furthermore, our molecule likely retains the advantages of high surface density (>10%) due its lengthy alkyl chain (17 carbons).

Figure #17: Comparison of the biodistribution of non-ionic lipid nanoparticles (LNs) vs. individual PEGylated lipid nanoparticles (PLNs)

IV Administration of 0.2 mL of PEGylated LNPs into mice. The near-infrared DiR fluorescent probe was utilized to investigate biodistribution from in vivo experiments. The mice were anesthetized through diethyl ether inhalation and placed in a chamber. Fluorescent images were obtained using an exposure time of 500ms, excitation filter of 684-729 nm, and emission filter of 745 nm.

Our proposed PEGylated LNP also demonstrates greater co-localization to the brain after systemic administration and reduced microglia response, as measured by filament length, diameter, and soma volume (Figure #18).

The inflammation mechanism is likely due to P2X7 signaling, which is an ion channel activated by ATP and is expressed on microglia. When activated by ATP, this receptor facilitates the influx of calcium ions and efflux of potassium, leading to a pro-inflammatory cascade involving caspase-1 and cytokines such as IL-1B.

The PEGylated LNPs seem to avoid meaningful activation of this P2X7 signaling pathway, potentially due to their hydrophilicity and the steric hindrance properties conferred by PEGylation. This steric barrier impedes protein adsorption and reduces opsonization/complement system activation, which improves stability (and therefore biodistribution to the brain) and impairs macrophage uptake.

Figure #18: Effect of PEGylated lipid nanoparticles on brain microglia activation

The authors utilized Cx3cr1GFP/+ mice (model where fractalkine neuronal receptor is substituted with GFP) to evaluate microglial morphological changes. The GFP+ population in the brain of Cx3cr1GFP/+ mice overlap with the brain cells that express markers for microglia. The authors measured filament length (c), mean diameter (d), and soma volume (e) of the microglia to determine if there was a varied response after LN or PLN administration.

Activated microglia exhibit reduced filament length - the cells become more round/flexible and are represented by an amoeboid shape. Thus, when activated, microglia in the brain are longer in their natural state and shorten; PLN coming in at a length closely comparable to the control (Figure #18 - Section C) is indicative of a potentially muted immune response.

Activation also results in increased diameter and soma volumes, due to increased metabolic demands and phagocytosis. Sections D and E in Figure #18 thus indicate that PLNs trigger an immune response more comparable to control settings via microglia activation, vs. more comparable LN’s.

Prior successful LNP construct designs are below - we believe selective incorporation of the PEGylated lipid (~1.5-1.6x ratio) will exhibit a muted immune response in vivo. Note - we must measure this muted response against possible tradeoffs to LNP specificity conferred by the inhibition of protein corona component uptake, given shielding by the PEGylated lipid construct itself.

The extra cholesterol tails stabilize the LNP membrane

We believe the incorporation of a cholesteryl tail will improve membrane stability, both for the structural integrity of the LNP during encapsulation and for fusion with the target cell membrane21. This is in addition to the traditional independent cholesterol included in lipid bilayers.

Cholesterol reduces the isomerizations of lipid acyl chains—or the transformation of the fatty acid chains from the trans (more stable) to the cis (less stable) conformation, and promotes the formation of lipid rafts (enriched regions of saturated acyl chains) to act as a bidirectional regulator of membrane fluidity.

At high temperatures, these interactions restrain the movement of the fatty acid chains of phospholipids to decrease fluidity, but at low temperatures, cholesterol prevents fatty acid chains from packing together and solidifying to increase fluidity. The changes in fluidity subsequently alter the bending and compressibility properties of the membranes, which slows down the lateral and rotational diffusion of lipids.

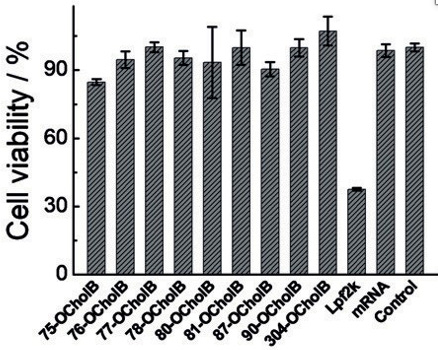

In vitro experiments demonstrated the improved viability of OCholB LNPs, compared to OChol and O16B LNPs in cytotoxicity tests. Further in vitro studies compared the induced cytotoxicity of the in vitro gold standard mRNA-lipofectamine to OCholB LNPs, and found that the cell viabilities were 37.5% (Lpf2k/Lipofectamine) and >84% respectively (OCholB).21

Figure #19: In vitro cytotoxicity experiments compared OCholB LNPs to lipofectamine

Note - Independent cholesterol molecules are also normally incorporated within lipid bilayer constructs. As shown by the image below, cholesterol molecules (a) have multiple effects on lipid bilayers. Cholesterol changes the (b) fluidity, (c) thickness, (d) compressibility, (e) water penetration, and (f) the intrinsic curvature of lipid bilayers. Cholesterol also induces (g) phase separations in multicomponent lipid mixtures, (h) partitions selectively between different coexisting lipid phases, and (i) causes integral membrane proteins to respond by changing conformation or (j) redistribution in the membrane.

Figure #20: Cholesterol Incorporation into standard LNP membranes

Section #1 | Part #7: Specificity from base editors

Base editing operates at the single nucleotide level, facilitating precise alteration of the genetic code without generating double-strand breaks or relying on the often unpredictable process of homology-directed repair. However, one of the critical parameters when considering the therapeutic potential of base editors is ensuring specificity.

Highly specific base editors create modifications on only the intended genomic site (on-target site), while minimizing unwanted alterations at alternate genomic sites (off-target effects). In particular when considering the delivery of base editors to sensitive tissues, such as those in the central nervous system, misdelivery or off-target activity could result in serious implications for an individual's health.

Off-target effects are categorized into sgRNA-dependent and sgRNA-independent edits. SgRNA-dependent off-target effects occur when the base editor is guided by its associated sgRNA to unintended sites in the genome that contain similar sequences to the intended target site. This form of off-target activity is a consequence of the inherent tolerance of the RNA-guided DNA-binding protein (such as Cas9 or Cas12) for mismatches between the sgRNA and the DNA target sequence. On the other hand, sgRNA-independent off-target effects result from the intrinsic activity of the deaminase enzyme component of the base editor, which can bind to and edit DNA independently of the sgRNA-guided sequence recognition.

Strategies to enhance the specificity of base editors and limit both categories of off-target effects include engineering modifications to the base editor proteins themselves, such as narrowing the deaminase window of activity or using truncated versions of guide RNAs. Additionally, optimization of delivery methods, such as LNP’s vs. viral vectors as proposed in this paper, can improve cell-type specificity, thereby limiting off-target effects.

In this section - we focus on the optimization of the mRNA-LNP delivery method as the ideal strategy. We believe that mRNA-LNP’s are the clear choice because: 1) On-target base editing and sgRNA-dependent off-target editing possess a stronger profile for mRNA vs. plasmid (DNA) delivery; 2) The half life of mRNA-LNPs are much lower than DNA forms (such as AAVs); and 3) mRNA is easier to encapsulate and manufacture than ribonucleoproteins (RNPs).

On-target base editing and sgRNA-dependent DNA off-target base editing for plasmid vs. mRNA delivery

Utilization of mRNA would drastically limit—but not completely eliminate—the risk of harmful off-target effects due to the substantially increased turnover of mRNA versus DNA. However, the increased turnover must not compromise editing efficiency.22 Gaudelli et al. (2017) tested this theory by comparing the editing efficiency and off-target profiles of plasmid (DNA) and mRNA-delivered base editors. They found that, across the board, mRNA delivered-base editors possess the same or better editing efficiency vs. plasmid delivery (82.8% mRNA vs 73.9% plasmid), but the mRNA delivery contained fewer off-target effects (Figure #21). Using plasmids and mRNA as a proxy for AAV and LNP delivery respectively, we believe that LNPs are the superior approach due to similar editing efficacy and reduced off-target effects. Few cells are highlighted below to aid in visual comparisons, but the effect is largely consistent across cell line columns.23

Figure #21: Accuracy of base editing constructs delivered as either plasmids or mRNA

Heat map demonstrating the on-target base editing specificity and off-target effects. On-target DNA editing frequencies for core ABE8 constructs versus ABE7 delivered as plasmid (a) and mRNA (b). SgRNA-dependent off-target DNA editing frequencies for ABE8 versus ABE7 delivered as plasmid (c) and mRNA (d).

Half-life of mRNA-LNP vs. episomal DNA (AAV)

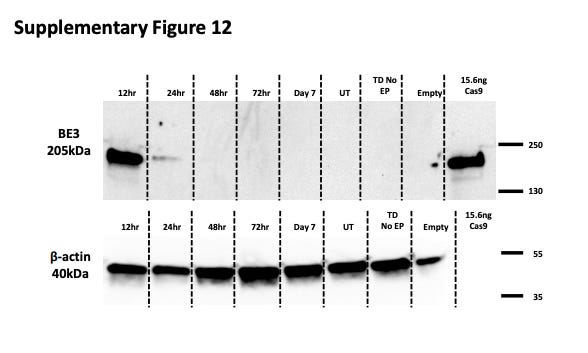

LNPs containing mRNA also demonstrate a much shorter half-life compared to episomal DNA in AAVs. Georgiadis et al. (2021) demonstrate that there is a significant (>50%) reduction in base editor quantity from 12 to 24 hours post-culture24, implying that the half-life is somewhere between 12 and 24 hours (Figure #22).

In contrast, Yang et al. (2018) report that the expression levels were significantly different between AAV-Cas9 and AAV-GCas9 at 3 weeks but roughly equivalent at 9 weeks. GCas9 is designed to increase the degradation rate of the Cas9 protein, thus the equivalence in protein presence is indicative of a rough half life estimate. Based on this expression profile, we can reasonably estimate that the half-life of Cas9 via AAV is in the order of weeks25 (Figure # 23).

Figure #22: Half-lives of mRNA base editors

Primary T cells were exposed to the mRNA of a base editor (BE3), comprising a deactivated Cas9 nickase fused to APOBEC1 (deaminase) and a single uracil glycosylase inhibitor (UGI). Then, cells were transduced with a Terminal-TRAC-CAR19 lentiviral vector. Cell lysates were collected 12, 24, 48, and 72 hours post culture and again on day 7.

Figure #23: Half-lives of DNA base editors

Yang et al. delivered AAV-Cas9 and AAV-GCas9 into the striatum of WT mice via stereotaxic surgery. GCas9 is a gemini tagged version of Cas9 meant to reduce the half-life because the expression is regulated by the cell cycle.25 Y-axis indicates the relative marker expression to vinculin for WT, Cas9, and GCas9, as determined by a quantitative analysis of Western Blots.

mRNA vs. RNP

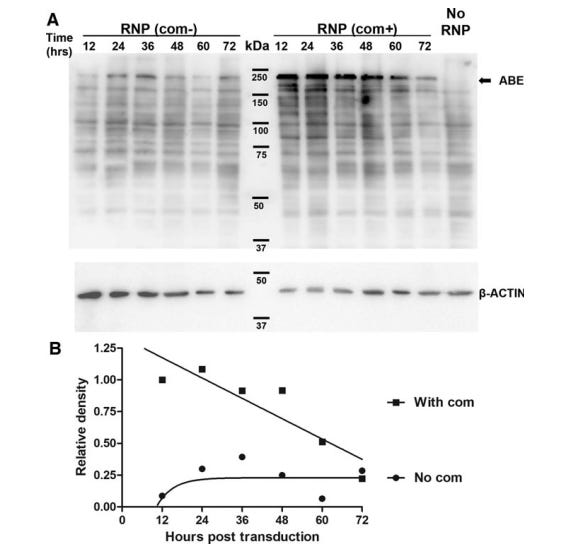

Furthermore, although RNPs are thought to have the shortest half-life and therefore the least # of off-target effects, it is likely in the same order of magnitude as mRNA half-life. One study demonstrated that the half life of ABE RNPs were ~36-40 hrs (Figure #24),26 compared to <24 hrs for mRNA in vivo as seen in the figure above (Figure #22).24

Figure #24: Half-life of ABE-RNP protein

Top panel - Western blotting analysis of ABE levels after transducing HEK293T cells with lentivirus in vitro. Bottom panel - the densitometry analysis of protein degradation from the western blot.

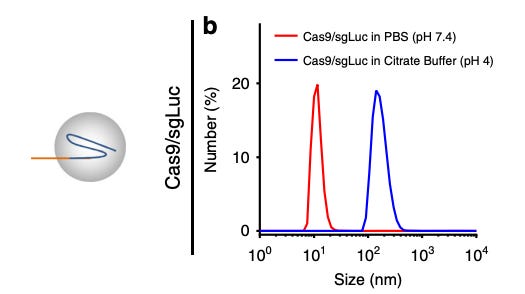

Additionally, RNPs are difficult to deliver via LNPs because of challenges with encapsulation. The RNP-gRNA complexes are large (10-15 nm), making it difficult to fit inside LNPs. Some scientists have found ways around this limitation. For example, Wei et al.27 developed a permanently cationic LNP formulation (1,2-dioleoyl-3-trimethylammonium-propane) to encapsulate RNP into LNP and deliver them to the muscle via intramuscular injections. However, RNPs denature in acidic conditions [Figure #25], which is concerning since intracellular compartments are more acidic than the bloodstream.

In addition, the sgRNA complexed to the RNP has a strong negative charge, which requires a permanently charged (rather than ionizable) cationic lipid to maintain stability.27 However, permanently charged cationic lipids are prone to degradation by Kupffer cells in the liver and splenic macrophages because the scavenger, toll-like, mannose, and Fc receptors target positive nanoparticles.

Finally, RNPs are notorious for being difficult to manufacture and purify because the RNPs are prone to degradation during the encapsulation phase. Every step of the protein production process - in particular expression and purification - requires extensive optimization for each new construct to maximize yield.22 Applying an existing protein production process to a novel construct is more time-consuming than optimizing mRNA production for a new sequence.

Therefore, mRNA remains the better choice for delivery.

Figure # 25: Denaturation of Cas9 RNPs in acidic buffer

In vitro experimentation testing the denaturation of Cas9 RNPs in PBS (basic) and citrate buffer (acidic). A larger size indicates that the protein has denatured and a smaller size correlates with reduced denaturation.

Delivering mRNA-LNPs is the modality of choice, since it maximizes editing efficacy while minimizing off-target effects due to the low half-life of mRNAs. Challenges with RNP encapsulation and reduced large-manufacturing capabilities also support the decision to deliver mRNA over RNPs. Taken together, the specificity of base editors aided by specificity from LNP’s and Live-MRI convection enhanced delivery (discussed in Section #2) will create a long term fix with minimal off-target effects.

Section #1 | Part #8: Conclusion

Bringing these facts together, while the research is still early, we can see a clear difference in specificity between our proposed LNP and AAV9 vectors. This creates the foundation for a highly specific distribution that, when combined with the inherent specificity characteristics of base editors - will enable us to deliver in vivo therapies targeted towards monogenic diseases. Specific monogenic neurological diseases, such as Spinal Muscular Atrophy, Rett Syndrome, and Familial Dysautonomia will benefit from focused LNP delivery to neurons ONLY vs. AAV’s.

We hypothesize that “stacking” the specificity characteristics of (1) LNP’s, (2) base editor technologies, and (3) ClearPoint Neuro’s Live-MRI guided therapy will significantly reduce the percent probability of a base editor-directed off target effect.

We see neuron-focused LNP’s as the first step of our platform buildout - there is evidence of LNP uptake in adjacent neuronal cells (i.e. astrocytes, microglia, oligodendrocytes) that will enable us to target other monogenic neuronal diseases: Metachromatic leukodystrophy (Oligodendrocytes), Gaucher disease (Microglia), and X Adrenoleukodystrophy (Oligodendrocytes).

Section #2: ClearPoint Neuro’s SmartFlow Cannula + SmartFrame Array technologies create efficient delivery rails into the brain

Section #2 | Part #1: Issues with standard neurological delivery mechanisms and our proposed solution

Standard neurological delivery mechanisms (intracranial/ICV injections) provide lackluster access to critical tissue areas within the brain, are prone to drug reflux (minimizes volume of drug uptake by target tissue), and do not allow for real-time monitoring of infusion, which enables accurate evaluation of biodistribution. Our proposed solution addresses these key concerns, and we believe opens up a clear pathway for the use of base editors within a neurological context.

Background: PTC Therapeutics’ Upstaza gene therapy drug received recent approval for the treatment of AADC deficiency in the EU, delivered through ClearPoint Neuro’s cannula system.28 ClearPoint’s system enables submillimeter delivery accuracy (<1mm) of drug infusate, with broad and uniform distribution out of the cannula.29 Based on precedent positive delivery data outcomes shared to date from Upstaza’s validated AAV-based gene therapy, we believe base editing mRNA constructs are a logical next step for applications in neurological diseases.

The Problem:

Controlling the distribution of key therapeutic agents is oftentimes the biggest issue when translating preclinical neurological results into clinical efficacy. Multiple variables influence variance in biodistribution, including: injection technique, location of the injection site in the brain, cell density, vascularization, and the extracellular matrix. Current methods, including IV delivery or intrathecal/intracerebroventricular injections, are unable to reliably navigate these constraints and deliver drug products with uncontrolled distribution. For example, ICV delivery of Brineura to treat neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis 2 (CLN2) disease utilizes incremental pressure to forcibly administer drugs by overcoming extracellular impediments. This in turn runs the risk of creating added drug reflux back into the delivery product, exacerbating issues surrounding delivery certainty and accuracy. Delivering intraputaminal injections via Clearpoint’s technologies enabled Upstaza to overcome these issues to address AADC deficiency. Additionally, surgeons are unable to fully visualize distribution accurately, which will create further issues as it pertains to precisely locating delivery targets within the brain—an ever more critical consideration as genetic medicines are applied in neurological contexts.

Section #2 | Part #2: Technical advantage - convection-enhanced delivery

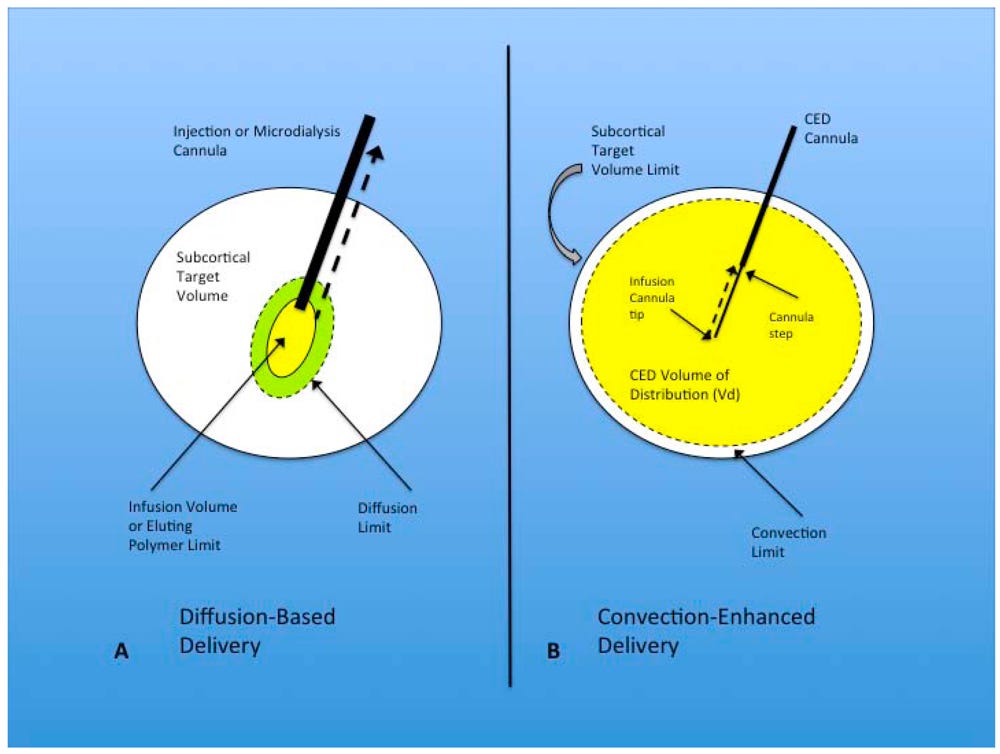

In the central nervous system (CNS), fluid movement is primarily governed by two mechanisms: diffusion and bulk flow. Diffusion is a process dependent on concentration gradients, as described by Fick's law: J (diffusive flux) = -D (tissue diffusivity) x ∆C (concentration gradient). However, diffusion is not an efficient method for the transport of macromolecular drugs in the CNS. Despite its dependence on high concentration gradients, the diffusion of these drugs is slow, and their effective penetration in brain tissue is limited to a few millimeters. Alternatively, bulk flow is driven by fluid pressure gradients within tissues, as characterized by Darcy's law: v (velocity of fluid) = -K (hydraulic conductivity) x ∆p (pressure gradient). Notably, the movement of therapeutic agents via bulk flow is independent of their molecular weight, thereby allowing equal distribution regardless of size. Additionally, bulk flow does not rely on a pure concentration gradient to drive molecule diffusion, enabling a broader distribution profile across brain tissue.

Convection-enhanced delivery (CED) exploits the principle of bulk flow by generating a positive pressure gradient via an automated pump. This method enables the distribution of high concentrations of macromolecules over substantial volumes within the brain parenchyma, thus maximizing drug dispersion. In this process, a cannula is positioned within the brain's interstitial spaces, and a controlled infusion is administered. Controlled infusions are essential for inducing bulk flows, capable of distributing the infusate over large volumes and achieving a spread of several centimeters. The transport of substances in this context depends on a combination of convection, diffusion, metabolism (how the drug is degraded/cleared), binding (affinity for nearby receptors or chaperone molecules), and net transport (movement through fluid). Unlike diffusion, which results in limited tissue penetration (1 to 2 mm) and a rapid concentration drop-off over a short distance (250 to 1000-fold), bulk flow supports a more homogenous distribution of the infusate [Figure #26].

The key metric that determines optimal delivery is the volume of distribution(Vd)/volume of infusion (Vi), which is ideally 3:1.

Figure #26: Convection-enhanced delivery utilizes a positive pressure gradient rather than a concentration gradient30

Diffusion-based delivery systems are the standard for neurological diseases today, which maximize concentration of drug delivered to enable gradual diffusion across brain tissue.

ClearPoint’s approach leverages convection-enhanced delivery which relies on a pressurized drug application that maximizes the Vd by creating a distribution gradient. Additionally, ClearPoint’s device utilizes a stepped cannula to minimize the risk of infusion backflow, which runs the risk of altering the actual amount of drug delivered in patients. This is important, given prior studies31 in neurological diseases failed specifically due to the surgeon’s lack of tools to verify consistent delivery quantities of drug across each time point.

The schematic above provides a visual example, comparing (a) diffusion-based delivery vs. (b) convection-enhanced delivery.

Section #2 | Part #3: Stepped cannulas limit reflux, a critical consideration for CED

CED was popularized in the 90s because of the shortcomings of manual delivery of infusates through a microsyringe, including limited coverage, lack of consistent flow rate, and unknown delivery concentration. At first, scientists utilized a short fused-silica catheter connected to a syringe pump by teflon tubing. They found that the teflon tubing had too much dead volume and would result in the adsorption of the vector. Teflon tubing and stainless steel cannulas were then lined with silica and reduced in diameter. However, there was still significant backflow with higher flow rates, which resulted in delivery of agents outside of the intended target. Stepped cannulas were then adopted to generate backflow-free delivery at higher flow rates [Figure #27].

However, even stepped cannulas have room for improvement. In one study,31 real-time MRI monitoring revealed that delivery of infusate through a stepped cannula resulted in leakage beyond the superior boundary of the putamen, particularly if there was extra side-to-side movement of the cannula. To address this issue of backflow and ensure that the second step of the cannula crossed the dorsal boundary of the putamen earlier, surgeons modified the cannula design to have a second bullet-shaped step 13 mm from the tip instead of 18 mm.

Figure #27: Stepped cannula design for neurosurgery

Schematic of varying sizes of stepped cannulas, which are crucial for limiting backflow.

The major benefit of stepped cannulas comes from their ability to prevent backflow of drug products upon administration. Multiple steps create a reservoir of fluid prior to each junction, where the pressure applied back against the fluid retains distribution in the key area of interest upon cannula release.

Section #2 | Part #4: Real-time imaging reduces complications by permitting detection of reflux, leakage, and adjustment of treatment delivery to reduce adverse effects

Real-time imaging data is Clearpoint’s final meaningful advantage in biologics drug delivery. The ability to fine-tune delivery accuracy during a procedure itself is a powerful advantage, ensuring consistency in the amount of drug dosage per protocol that is delivered to each patient served.

Real-time imaging permits quantification of the Convection Enhanced Delivery (CED) dynamics and intraoperative detection of reflux and leakage, thus enabling live adjustments to surgical procedures to reduce complications and improve vector distribution. Real-time imaging also confirms that the area of drug delivery is equivalent to the area of vector transduction as seen through MRI’s.

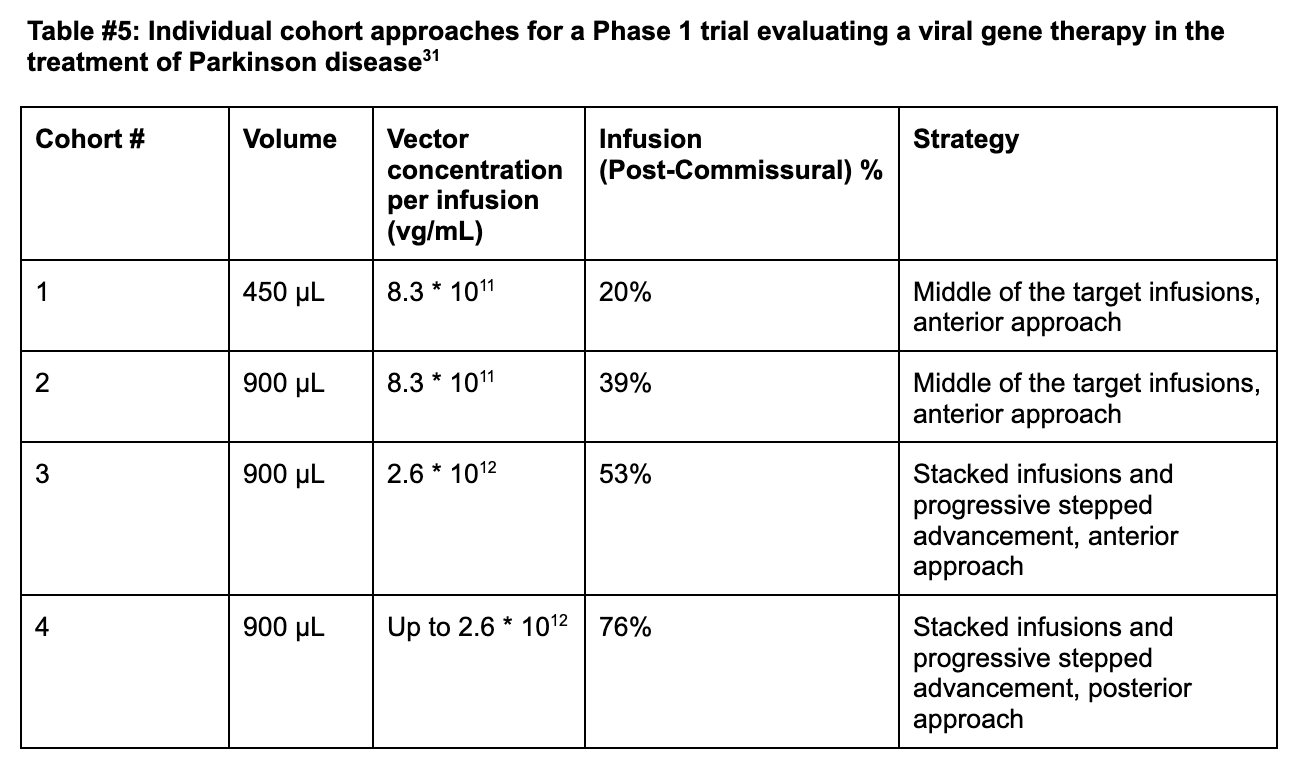

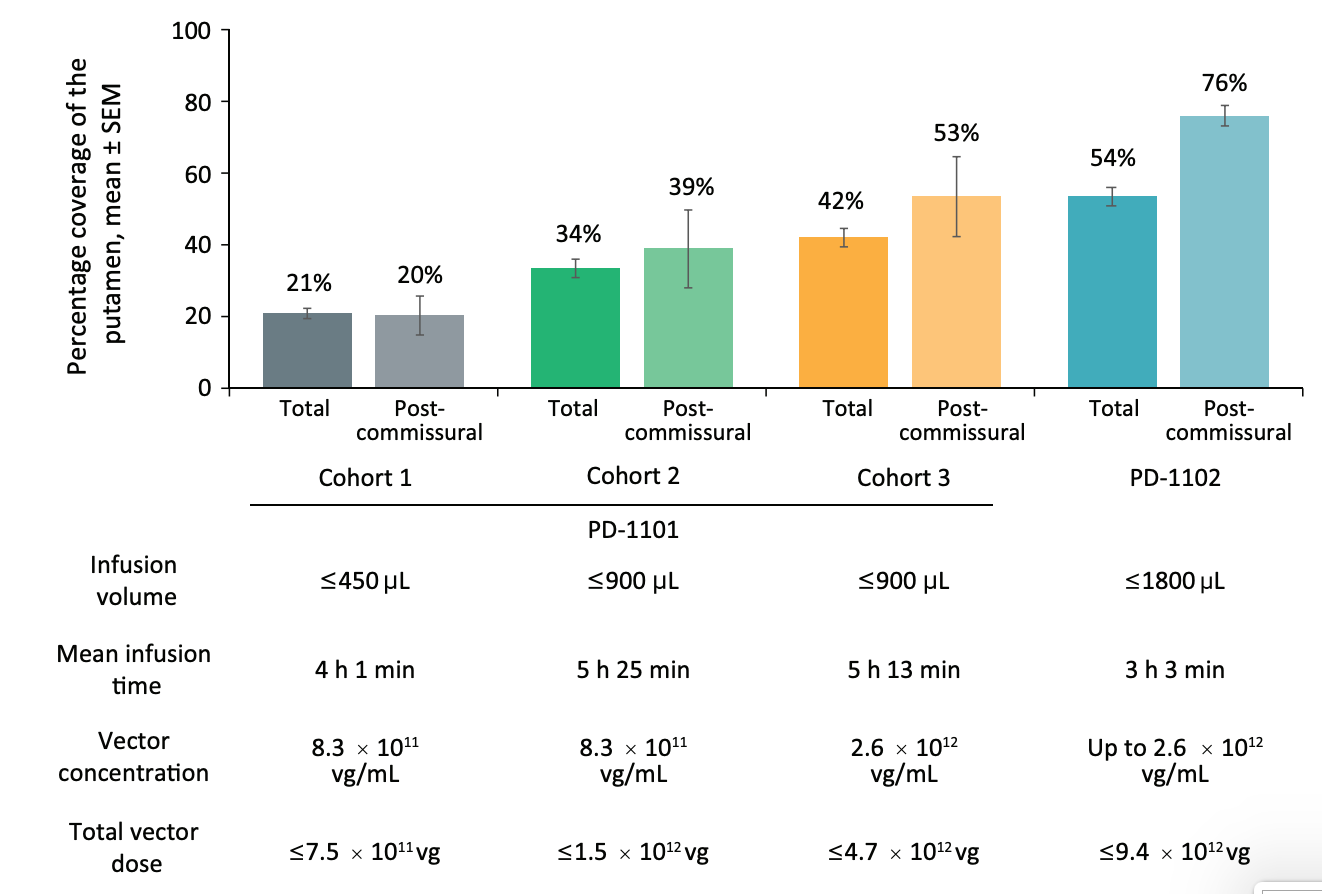

Delivery data from various cohorts in a single trial utilizing Live-MRI CED delivery volumes

The following section highlights how progressive improvements to CED delivery methodology resulted in meaningful step-ups to infusion efficacy with a viral vector delivering aromatic L-amino acid decarboxylase (AAV2-hAADC). The clinical trials (PD-1101 and PD-1102) investigated the administration of AAV2-hAADC in patients with advanced PD and medically refractory motor fluctuations.

Cohort 1 (Anterior Delivery + Standard infusion): Coverage remained limited at +21% in cohort 1 of PD-1101 administering 8.3*1011 vg/mL of AAV2-hAADC, well below the 35% efficacy threshold required in the postcommissural putamen (the sensorimotor portion).31

Cohort 2 (Anterior Delivery + 2x Standard infusion): Researchers doubled the infusate volume from 450 µL to 900 µL at the same concentration and found an improved coverage of +34% (39% post-comissural) [Figures #28, #29; Table #5].

Cohort 3 (Anterior Delivery + Stacked Infusions + Continuous Infusion): Live-MRI monitoring enabled the surgeons to identify previously unrecognized perivascular leakage into adjacent neural structures from prior cohorts. Perivascular spaces are areas around arterioles, capillaries, and venules in the brain, through which fluid or particles can pass through. The surgeons also identified unwanted backflow of drug product receding through the cannula tracks which reduced the amount of drug actually delivered to the patient, and created an inconsistent level of delivery during each treatment episode. In response, the surgeons employed stacked infusions, which consists of advancing the cannula deeper into the tissue upon initial administration to deploy a second dose, which reduces overall leakage in the system.

Stacked infusions consist of two infusions, with the proximal point administered first, past the perivascular space, and the distal point second (deeper than the first infusion). In this cohort - researchers then increased the vector concentration of each infusion to 2.6 * 1012 vg/mL and found a total coverage of 42% and post-commissural coverage of 53%.

Notably, for the last eight patients in this cohort, surgeons realized that administration into the putamen could be optimized further beyond just stacked infusions. The team adopted a progressive stepped advancement technique. This technique consists of continuous infusion (2.6 * 1012 vg/mL) as the surgeon slowly advances the cannula deeper into the brain, enabling clinicians to fill the putamen as uniformly as possible and helping to move the cannula tip away from perivascular spaces [Figures #28, #29; Table #5].

Cohort 4 (Posterior Delivery + Stacked Infusions + Continuous Infusions): The surgeons included a posterior delivery approach which drastically improved postcommissural coverage of the putamen to 76% at the same concentration as cohort 3 (2.6 * 1016 vg/mL) [Figures #28, #29; Table #5].

Figure #28: Delivery and distribution data using CLPT Neuro’s system (Cohorts in the figure below match cohort #’s from the table above).

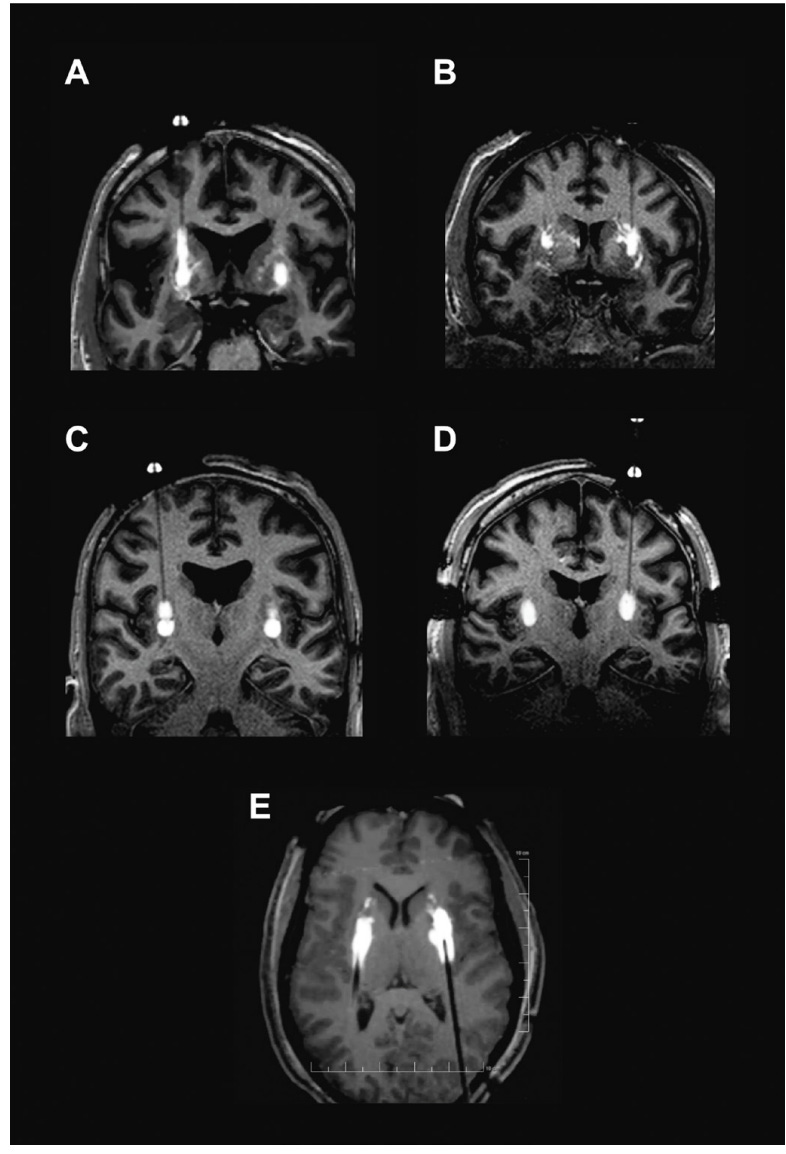

Figure #29 below seeks to visually confirm the distribution of the drug via cannula administration to the brain. Images showcase results from the PD-1101 trial of backflow (Image A), perivascular leakage (Image B), stacked infusions (Image C), and progressive stepped advancement administration (Image D).

Figure #29: MRI images showcasing intraoperative monitoring of the administration of a viral vector mixed with gadoteridol (contrast) into Parkinson’s Disease patients

A - Backflow up cannula track

B - Perivascular and off-target leakage

C - Stacked infusions

D - Progressive stepped advancement

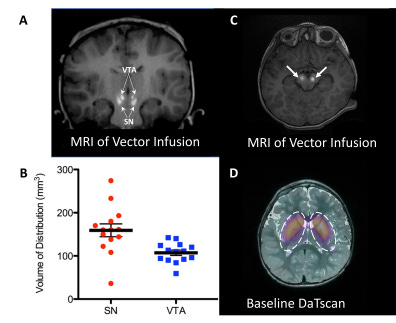

Section #2 | Part #5: AAV gene therapy delivery and distribution data using Clearpoint Neuro’s system

Data shared by PTC Therapeutics to date confirms the efficacy profile achieved by Upstaza therapy via Clearpoint’s delivery methods.

Figure #30: Delivery of AAV gene therapy (Upstaza) via Clearpoint’s Live-MRI approach

MRI-guided delivery of AAV2-hAADc into the midbrain, specifically the substantia nigra (SN) and ventral tegmental area (VTA) . Images shown include coronal (a) and axial images (c) of vector infusions. Bright signal corresponds with contrast (gadoteridol) mixed with AAV2-hAADC. The infusions were performed sequentially while imaging, starting with the right SN. In panel B, the coverage (Vd) is examined for each target structure. Panel D demonstrates DaTscan imaging of the striatum at baseline to confirm a regular dopaminergic pathway in study subjects (the scan measures dopamine transporter, DAT).28 Using real-time MRI images, the authors were able to confirm the accurate placement of the infusion catheter at each target (bilateral SN and VTA) for all 7 subjects. There were two dose groups: 1) 8.3 * 1011 vg/mL (n = 3); and 2) 2.6 * 1012 vg/mL (n = 4). The pattern of distribution followed an oval shape surrounding the catheter tip. There were two infusions performed (left and right) for each site. Each participant was infused with 160 µL of vector (100 µL into SN and 30 µL into VTA).

The authors found that infusion of 50 µL into the SN resulted in mean drug coverage of 160 +/-60 mm3. Infusion of 30 µL into VTA resulted in mean drug coverage of 103 +/- 22 mm3 (n = 14). Vd/Vi was ~3.2 in SN (160mm3/50µL) and ~3.4 in VTA (103mm3/30µL). Coverage volume suggests almost 80% anatomical coverage of both SN and VTA in all subjects (Figure #30).

Leveraging its inherent advantages, ClearPoint’s technology has proved, with an on-market drug, that it’s able to allow surgeons to optimize the Vd/Vi ratio. This optimization is of paramount significance, particularly in the context of rare neurological diseases such as SMA, given that approximately 20% of motor neurons in this condition must uptake the therapeutic agent to elicit a clinically observable effect.32

Section #3: Evidence of Base Editing in Neurodegenerative Disease

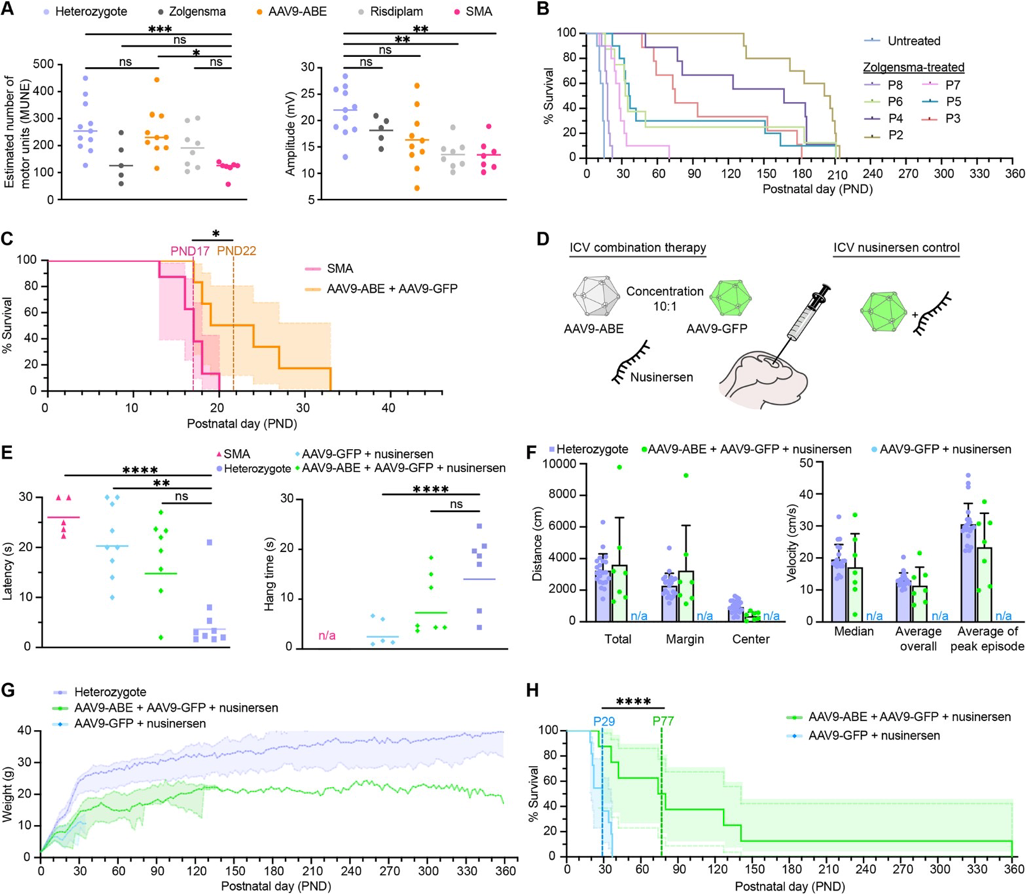

We’ve recently seen the successful in vivo application of base editors in mice with Spinal Muscular Atrophy (SMA) by the Liu Lab.33 We hope to take this proof of concept and expand to adjacent, genetically driven neurological diseases.

SMA is a neurological disorder that affects spinal motor neurons, the cells that control movement. It is caused by a mutation in the SMN1 gene. SMN1 is essential for the survival and function of motor neurons. SMN2 is an almost identical gene to SMN1 that differs at a single nucleotide in exon 7, leading to skipping of exon 7 in most SMN2 transcripts and resulting in a truncated, unstable protein. Arbab et al. (2023) demonstrated that base editing of the SMN2 C6>T mutation restored SMN protein levels to wild type.33 In addition, AAV9-mediated base editor delivery into a SMA mouse model yielded 87% T6>C conversion (Figure #32), improved motor function, and an enhanced lifespan of 111 days (nusinersen + base editor) vs. 28 days (nusinersen alone) (Figure #33).

This additive effect likely occurs due to nusinersen extending the therapeutic window. Per Arbab et al. (2023), therapeutic intervention can improve disease outcomes in humans if administered within the first few months of life. In mice, that window is shortened from a few months to 6 days due to the ~150-fold greater rate of maturation in the first month, leading to a reduction in SMN expression and loss of motor neuron function. In vivo base editing takes ~1-3 weeks34 to impact protein levels since there are numerous steps before the gene editing occurs: 1) Second strand synthesis of AAV9-ABE genome; 2) Transcription and translation of split intein ABE protein segments; 3) Assembly and trans splicing of split ABE protein; 4) RNP assembly and base editing of SMN2; 5) Transcription of full length C6T modified endogenous SMN2 pre-mRNA driven by the native promoter; and 6) Splicing and translation of corrected SMN2 transcripts. Nusinersen leads to improved exon 7 inclusion (Figure #31), which increases SMN2 protein stability and likely enhances the survival of the mice.

Figure #31: Schematic of Nusinersen’s mechanism of action to improve exon 7 inclusion

There are three FDA approved treatments for SMA: 1) Nusinersen; 2) Risdiplam; and 3) Zolgensma. Current treatments do not restore endogenous protein levels and utilize non-native methods of regulation of SMN, which could result in pathogenic SMN insufficiency or long term toxicity. Also, nusinersen and risdiplam require repeated dosing throughout the patient’s lifetime. It is unclear whether Zolgensma activity will persist, and there are early hints at potential toxicity due to two recent deaths 35 from liver toxicity.

Figure #32: Adenine base editing in Δ7SMA mice

The authors ICV administered 2.7 *1013 vg/kg AAV9-ABE vectors into SMA neonates along with 2.7 * 1012 vg/kg AAV9-Cbh-eGFP-KASH. They then performed CIRCLE-seq to determine editing efficacy. They found 87 +/- 3.5% average on-target editing of SMN2 among GFP-positive cells in the CNS.

Figure #33: AAV9-ABE mediated rescue of Δ7SMA mice

The authors ICV administered 2.7 *1013 vg/kg AAV9-ABE vectors into SMA neonates along with 2.7 * 1012 vg/kg AAV9-Cbh-eGFP-KASH. They then performed CIRCLE-seq to determine editing efficacy. They found that the combination treatment of AAV9-ABE with nusinersen significantly enhanced survival outcomes to 111 days (compared to 28 days nusinersen alone) and demonstrated a maximum lifespan of 260 days (compared to 37 days nusinersen alone).

Overall, we strongly believe in the potential of utilizing base editing to treat rare, monogenic neurological diseases. We hope to build off of the work from Arbab et al. (2023) and add additional specificity benefits from LNP and Live-MRI technologies to achieve monogenic disease cures.

Section #4: Future Indications Where we Will Apply the Platform Technology

Section #4 | Part #1: Pipeline of target diseases

Despite their individual scarcity, rare diseases cumulatively afflict more than 300 million individuals globally, posing a substantial healthcare challenge and societal burden, with a significant proportion of these conditions—nearly half—being neurological in nature.

Additionally - an overwhelming 90% of pediatric-onset rare diseases demonstrate neurological sequelae. These disorders frequently emerge early in life, substantially undermining the patient's quality of life, and precipitating premature mortality. Regrettably, the vast majority of these conditions lack efficacious treatments, attributable in part to their intricate pathophysiology, the complexities inherent in delivering therapeutics to the brain, and the constrained commercial appeal of devising treatments for small populations.

Nevertheless, the landscape continues to rapidly evolve, largely due to the advent of innovative therapeutic strategies such as base editing. Despite this potential, the translation of base editors from the bench to the bedside remains challenging due to the continued need of base editor gRNA refinement and the creation of delivery mechanisms capable of proficiently transporting the base editors across the blood-brain barrier.

Our proposition involves leveraging base editors to target seven distinct rare neurologic diseases, with a bias to pediatric conditions, thereby providing long-term treatments for this distinctly underserved population. We arrived at these indications following an analysis of a panel of monogenic rare neurological diseases, predominantly pediatric, and evaluating them based on several crucial metrics:

Life expectancy, with preference for more lethal conditions;

Strong genotype-phenotype correlation

Presence of mutations with a frequency with a significant plurality

Proportion of the population treatable with base editing

Disease incidence

The competition landscape.

Guided by this framework, we identified the following conditions as prime opportunities to develop base editing treatments for neurological diseases:

Spinal Muscular Atrophy (SMA)

Rett Syndrome

Familial Dysautonomia

GM1 Gangliosidosis

Niemann Pick Disease Type C

Dravet Syndrome

Mucopolysaccharidosis Type 1 (Hurler Syndrome).

Section #4 | Part #2: Disease physiology and regions of interest we will seek to target

Spinal Muscular Atrophy (SMA)

Cause of Disease: Mutations in SMN1 gene

Purpose of SMN1 Gene:

SMN1 provides instructions for the survival motor neuron (SMN) protein, which is essential for RNA metabolism through the interaction with RNP complexes. SMN regulates the genesis of small nuclear RNPs, small nucleolar RNPs, small Cajal body-associated RNPs, signal recognition particles, and telomerase. Taken together, SMN plays crucial roles in DNA repair, transcription, pre-mRNA splicing, histone mRNA processing, translation, selenoprotein synthesis, and cytoskeleton maintenance.

Approximately 96% of cases are caused by homozygous absence of SMN1. However, SMN2 partially compensates for the loss of SMN1 and differs only by a silent C*G to T*A substitute at nucleotide position 6 of exon 7, which results in the skipping of exon 7 in SMN2 mRNA transcripts. The inclusion of exon 7 codes for a fully functional protein domain for the full-length SMN protein.

Kinetics of Disease and Proposed Adjacent Edits:

Cas9 proteins that either restore the C6T edit back to its normal state, or that disrupt editing of the splicing region, result in restored exon7 inclusion and functional protein.

The most successful base editing strategy was the C6T (>25x ABE SMN protein overexpression) mutation reversion by the ABE8e construct (i.e. direct mutation of the base gene DNA vs. influencing alternate regulators).

Rett:

Cause of Disease: Mutation in Methyl CpG binding protein 2 (MeCP2)

Purpose of MeCP2 Gene:

MeCP2 is involved in the remodeling of chromatin through affecting methylation. It interacts with transcription factors, chromatin modifiers, and RNA-binding proteins to facilitate changes in chromatin structure and accessibility to transcriptional machinery. The methyl-CpG-binding (MBD) domain of the MeCP2 protein will recognize and bind 5-mC regions. There is evidence that MeCP2 both activates and represses various genes.

~70% of mutations arise from C-T transitions at 8 separate CpG dinucleotide regions.

Kinetics of Disease and Proposed Adjacent Edits:

We aim to utilize ABE’s to create direct edits and fix the C-T mutation, which avoids the complications of MECP2 duplication syndrome from overexpression of MECP2 (Possible challenge associated with existing therapies seeking to overexpress MECP2).

Familial Dysautonomia

Cause of Disease: Mutation in IKBKAP gene (98% of patients have this mutation)

Purpose of IKBKAP Gene:

IKBKAP encodes IKAP, also known as Elongator Complex Protein 1 (ELP1). ELP1 plays a key role in the six-protein elongator complex, which is involved with RNA polymerase II transcriptional activity and histone acetylation. In the cytoplasm, ELP1 is involved in cell migration, intracellular trafficking, tRNA modification, cytoplasm kinase signaling, and p53 activation.

~98% of individuals (mostly of Ashkenazi Jewish descent) are homozygous for IVS20+6T>C. This mutation involves the base pairing of the U1 small nuclear ribonucleic protein to the intron 20 donor splice site, resulting in the skipping of exon 20. The resulting frameshift constitutes a truncated 79 kDA protein.

Kinetics of Disease and Proposed Adjacent Edits:

Since almost all the patients have the same T>C transition, this disease is ideal for utilizing a CBE to edit IVS20+6C>T, thus fixing the mutation and resulting in repaired protein production.

The established treatments have been only mildly effective. Kinetic (6-furfurylaminopurine), a plant cytokinin, was shown to facilitate the production of a full mRNA transcript by fixing splicing. One clinical trial found that 23.5 mg/kg of kinetin administered to 8 patients for 28 days resulted in an improvement of full length ELP1 mRNA from 54% (day 0) to 57% (day 8) and 71% (day 28).

GM1 Gangliosidosis

Cause of the Disease: Mutation in GLB1

Purpose of GLB1 gene

GLB1 codes for the beta-galactosidase protein, an enzyme located in lysosomes. Absent or reduced beta-galactosidase activity leads to the accumulation of B-linked galactose-containing glycoconjugates including glycosphingolipid (GSL) GM-1 ganglioside in neuronal tissue. GSLs normally reside in the plasma membrane and are involved in the modulation of signal transduction. GSLs are thought to be crucial for neurodevelopment, neuronal plasticity, and neuritogenesis. The buildup of GM1 ganglioside leads to lysosomal dysfunction, dysregulation calcium homeostasis, and cell death.

82% of the gene alterations are SNVs, 60% are missense mutations, and ~11% are frameshift.

~41% could be targeted by ABE. One example of a common mutation is c.145C>T.

Kinetics of Disease and Proposed Adjacent Edits:

This disease is characterized by 82% SNVs, most of which can be targeted by base editing, making it an ideal target. For example, we could utilize ABE to convert GLB1 145T>C.

In addition, there are only a few gene therapy trials (AAV-mediated) in progress, and we believe base editing is a better approach because you can fix the core issue and maintain endogenous regulation of the gene.

Niemann Pick

Cause of the Disease: Mutations in the NPC1 or NPC2

Purpose of NPC1/NPC2 genes

NPC1 and NPC2 proteins are involved in the intracellular transport and metabolism of cholesterol and other lipids. After endocytosis, low density lipoprotein (LDL) is delivered to the lysosome, where acid lipase cleaves cholesterol esters to form free cholesterol. NPC2 (~25 kDA) binds to cholesterol and transfers it to NPC1 (1278-residue protein). Mutation of these proteins leads to massive accumulation of cholesterol and glycosphingolipids in lysosomes of tissues.

3344T>C is a mutation in ~20% of western europeans and ~15% of the US population. In addition, it’s estimated that ~50% of patients in Brazil have targetable mutations such as 3104C>T.

Kinetics of Disease and Proposed Adjacent Edits:

We propose utilizing CBE and/or ABE to edit specific mutations (e.g., 3344T>C and 3104C>T).

The primary treatment is off-label Zavesca (approved for Gaucher disease). There are currently no approved treatments for Niemann-Pick Type C disease.

Dravet Syndrome:

Cause of the Disease: Mutations in SCN1A

Purpose of SCN1A gene

SCN1A encodes the alpha subunit of the voltage-gated sodium channel (VGSC) Nav1.1. These sodium channels contribute to the initiation and propagation of action potentials in excitable neurons. In Dravet syndrome, mutations in the VGSCs of inhibitory neurons lead to excessive excitation of action potentials and seizures. Approximately ~70-80% of children with the disease have a mutation in this gene.

There are >500 known mutations causing Dravet syndrome. Out of these mutations, ~40% are truncating, 40% missense, and 90% de novo. One of the most common mutations is 2588T>C.

Kinetics of Disease and Proposed Adjacent Edits:

We propose direct editing by utilizing CBE to convert 2588C>T. Dravet syndrome is a favorable target because of the fatality of the disease (10-20% of children die before adulthood).

Mucopolysaccharidosis Type 1 (Hurler)

Cause of the Disease: Mutations in IDUA

Purpose of IDUA gene

IDUA encodes the enzyme alpha-L-iduronidase, an enzyme that hydrolyzes the terminal alpha-L-iduronic acid residues of two glycosaminoglycans (dermatan sulfate and heparan sulfate). Loss of function in this gene leads to glycosaminoglycan accumulation throughout the peripheral organs and CNS, causing toxicity and cell death.

One of the most common mutations includes 1205G>A (W402X). This mutation is a single base substitution that introduces a stop codon at position 402, and is associated with a severe clinical phenotype—leading to death before age 10.

Kinetics of Disease and Proposed Adjacent Edits:

We propose direct editing by utilizing ABE to convert 1205A>G. Hurler syndrome is a favorable target because of the fatality of the disease, where most children don’t live past 10 years.

The major competition is RGX-111 (Regenxbio), an AAV9 vector encoding IDUA enzyme delivered to the CNS, and Aldurazyme, an enzyme replacement therapy. For similar reasons to other diseases, we believe the best toxicity profile will come from a treatment that is a direct fix adherent to native genome regulation mechanisms rather than non-endogenous sources of enzyme production.

Section #4 | Part #3: Proposed Guide RNA construct design

In the section below, we propose specific sgRNA constructs that we believe will serve to address the underlying mutations under each disease. Additional research we will conduct will open up the TAM for each indication to target regulatory elements, splicing regions, and TF binding domains to increase the # of pts we can treat who lack the dominant mutation for a specific indication.

Note: This is the key area of investment where we propose allocating $’s in our research studies to interrogate these rare diseases. Our goal was to design sgRNAs that contain the mutation of interest within the 4-8 nt base editor window region, which maximizes the efficiency of base editing for both cytosine and adenine base editors.

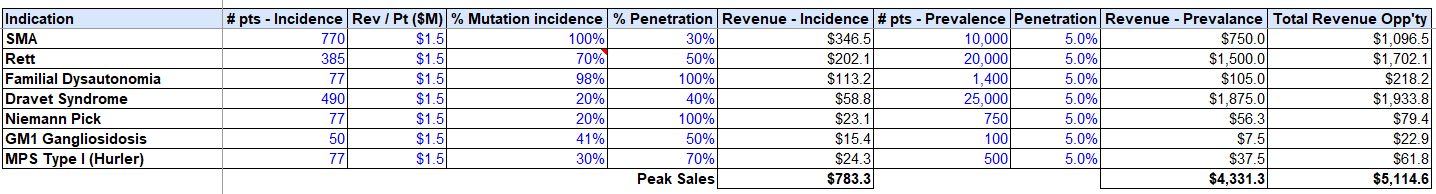

Section #4 | Part #4: Projected market opportunity and valuation

We can build to $5B in total revenue on conservative penetration assumptions based on our priority indications, while only targeting the direct mutations afflicting these conditions, vs. alternate regulatory elements / TF’s, etc.

Assuming fixed SG&A resource burn analogous to PTC Therapeutics, ~$100M per rare disease trial (higher end of the range per IQVIA trial estimates), and a 75% Gross Profit on each drug, we can build to 40% cash flow IRR’s, with the conservative prevalence penetration assumptions assumed above (5% of total market).

Risks to our Thesis

Despite the remarkable potential of base editing technologies, the application of these technologies for the treatment of neurological disorders is not without risks and challenges.

Off-target effects in Base Editors